A Mother, A Son, and A Wartime Secret

Selma had no social media presence and no listed phone number, but a $4.99 People Search brought up an address in upstate New York. I wrote her a letter, dropped it in a mailbox, and hoped for the best. I had heard that she wanted to put the past behind her and I didn’t know if she would want to talk to me. It had been more than 20 years.

Three days later, my phone rang. Selma wanted to see me.

To protect her privacy, I am not naming the town she lives in, and Selma is a pseudonym. I had not seen her since 1996 when I was reporting a story for Newsweek about rape and the children born from it during the war in Bosnia.

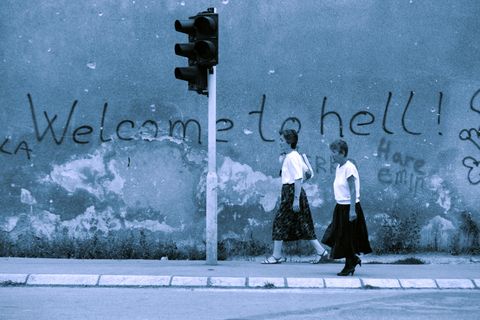

Back then, Selma was living in a ruin of an apartment on the outskirts of battle-scarred Sarajevo. Tormented and destitute, she counted herself as one of what was estimated to be more than 20,000 women who were raped during the four-year conflict. She had become pregnant and given birth to a baby boy. She saw the baby as an extension of the man she says raped her, a reminder of the pain and torture she had endured. “When I heard him cry, I asked the doctor to bring him to me. I wanted to strangle him,” she told me then. She left the baby at the hospital and tried to go on with her life.

In New York, it appeared that she had succeeded in doing so. She was married now, with two American-born teenagers. They lived in a tidy three-story house, with a garden. Selma cooked a lunch of chicken, rice, and broccoli, flavored with Chinese spices, followed by a spread of cookies, pastries, and coffee. She showed me photographs chronicling her life over the past couple of decades in the United States—the births of her children, picnics in the park, visiting Bosnian friends in New York City. The photos were organized in albums, neatly labeled by date. She said her life was good in New York—she felt safe and was grateful for her husband and children.

But as the afternoon wore on it became clear to me that Selma had not found peace. As we chatted about what had transpired over the years—we had both married and had children—Selma was calm, engaging, polite. But when I brought up Bosnia, she grew agitated. She said she felt betrayed, not just by what happened during the war, but by the post-war institutions that were supposed to help her. The aid organizations that flooded in to Bosnia after the war didn’t help her. The Association of Women Victims of War in Bosnia, which campaigns for the rights of women who were raped, didn’t help her. “None of them did anything for me,” she said. “The only one who ever did anything for me was God, because God sent me my husband and he has taken care of me.”

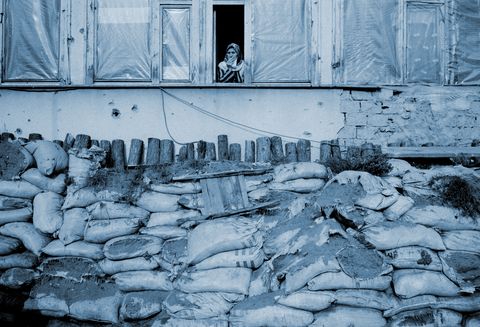

In between cigarettes—her fingers trembling as she smoked—she gestured for her husband to hand her the bag of pills sitting on the table. She was struggling with multiple ailments. I learned that she rarely left the house, and was never left alone. Her husband, who worked nights, stayed with her during the day. Her kids, who went to school during the day, stayed with her at night.

When we first met, back in 1996, Selma told me that she wanted her alleged rapist to stand trial for war crimes. She knew his name—he had been a neighbor, a married man with a grown child. She wanted the baby to be used as evidence in a war-crimes trial, so, from a distance, she kept tabs on what became of him. At the time, this sounded like a pipe dream. The United Nations had established a war-crimes tribunal, but the tribunal planned to focus on high-ranking suspects—those who planned and executed the crimes. Selma’s alleged rapist was a foot soldier. And although rape has been used as a weapon of war since time immemorial—Homer’s Iliad opens with a discussion of rape as a military tactic—no one had ever been prosecuted for it as a war crime.

The United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia would change all of that. It was the first international effort to prosecute war crimes since World War II, and the first court in history to explicitly recognize rape as a war crime. Both the U.N. tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the U.N. International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, which was established a year later, successfully prosecuted wartime leaders for rape. In doing so, they set far-reaching precedents, including prosecutions for mass rape at the International Criminal Court, which was established in 2002.

I had recently learned that Selma’s alleged rapist had, in fact, been put on trial, not at the U.N. tribunal but at its successor court, a special war-crimes chamber in Sarajevo that was staffed with international judges. More than 10 years after the rape, Selma had returned to Bosnia to testify. DNA from the child she left at the hospital was submitted as evidence, and Selma’s rapist was convicted. But he appealed and was acquitted. The reversal—in proceedings sharply criticized by legal observers from international monitoring organizations—sent Selma spiraling into despair. The accused, meanwhile, became a free man who has since denied that he fathered a child during the war.

I had asked to come to Selma’s house because I wanted to write about the case. I hoped, I suppose, that doing so might provide Selma some solace, some recognition that the process had not been fair to her. I suspect she invited me to visit in the same hope. But as the hours passed, it became clear that Selma was tormented by more than a verdict. I realized that there were things I knew that she had not told her husband. There were things they both knew but had kept from their children. There were now so many layers of omission, secrets, and pain it seemed it might be impossible to sort truth from whatever fills its absence.

Meanwhile, across the ocean, in the beleaguered Balkan nation she fled, the child Selma left behind had grown up and was on his own search for truth. That search was threatening to reveal her secrets, and possibly unravel the family that was holding her together.

Selma

Selma’s story began in a bleak coal-mining town in Bosnia, which was not yet a country when it lurched into war in the early 1990s. For most of the 20th Century, Bosnia was a republic in Yugoslavia, a Communist country whose name translates as land of southern Slavs. Its three main groups, Muslims, Croats, and Serbs, all lived in Selma’s town. But in April 1992, shortly after Bosnia declared independence from Yugoslavia, Serb forces took control and began killing or driving out all non-Serbs, a process known as ethnic cleansing. Muslims and Croats were put under house arrest. Their phone lines were cut. Serb paramilitary forces then made their way through town rounding up the men. Many of the women were taken to “rape camps.”

Serb forces came for Selma’s father that spring. She never saw him again. The following day, Selma said, a neighbor appeared at her door and said she had received a phone call. The caller said that Selma needed to give a statement at military headquarters and that someone would be coming to her family’s apartment to take her there. The soldier who came for Selma was, she says, someone she knew by sight. Instead of taking her to the military headquarters, which was a ruse, he took her to his apartment and forced himself on her. When he was done, he threatened to kill her if she told anyone. Over the next three months, he sent for her several more times. After the last time, he told her he was leaving town to visit his wife and child, who were in neighboring Montenegro. He assured Selma that nothing bad would happen to her while he was gone.

A few days later, Selma, her mother, her sister, and the rest of the area’s Muslim population were forced out of their homes and sent to Goražde, a nearby town held by Bosnian forces. Goražde was overrun with displaced people from other areas and had swelled to twice its pre-war population. It was surrounded by Serb forces, which had cut off its water and electricity supply and were shelling it from every direction. Food was in short supply because the Serbs controlled all roads leading in and out.

It was there—displaced, her father presumed dead, crammed into a makeshift shelter with little to eat or drink and artillery and sniper fire raining down on the town—that Selma realized she was pregnant. Had she not been overwhelmed with grief, fear, and shame, and had Goražde’s hospital not been overrun with war casualties it was ill-equipped to treat, she might have tried to get an abortion. As it was, she didn’t have the agency to do so.

For a time, Selma hid her pregnancy from her mother and sister, hoping she would miscarry. She considered killing herself. “I thought I could throw myself into the Drina,” she said, referring to the fast-flowing green river that runs through Goražde. She gave birth in February 1993 in a freezing cold hospital that was under siege. She was relieved when it was over, and keen to put as much distance as possible between her and the baby she saw as the manifestation of the horrors she endured.

It was a few months after Selma left the baby at the hospital that the U.N. announced the establishment of the war-crimes tribunal in The Hague, Netherlands. Everyone in Bosnia heard the news, including Selma. World leaders proclaimed that the U.N. tribunal would put an end to impunity and usher in a new age of accountability. Accountability was what Selma wanted more than anything in the world. “He has wounded me in a way that I will never heal,” she said about her alleged rapist. She said she wanted to see him in The Hague.

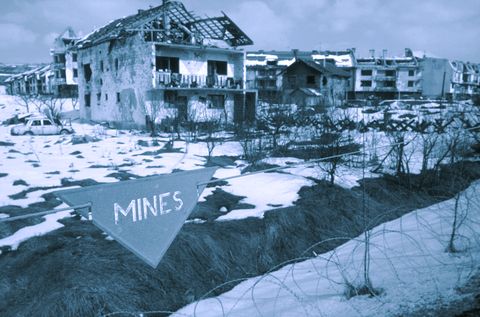

Alen

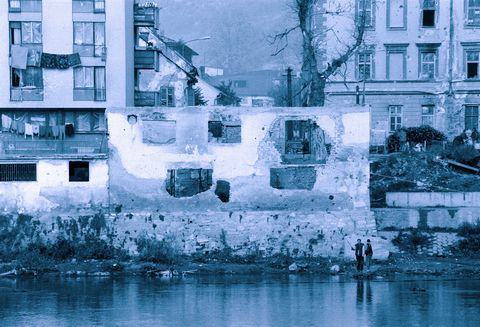

February 1993 was not a good time to be born in Goražde. Almost every building had been shelled, many of them several times over. The once-industrial riverside town was now a panorama of gutted and burned structures where amputees and other war wounded spent their days searching for food and water, and wood to burn for heat. Its inhabitants were emaciated. Over the first 10 months of siege, average adult weight loss was about 30 pounds.

Nobody was in a position to take in a newborn—especially not one that was understood to be the offspring of a Serb rapist, a story that quickly spread from the hospital and became known around town. But the hospital’s maintenance man, who had grown up an orphan, took pity on the malnourished infant. Muharem Muhic was in his late 40s and had two grown daughters. Serb troops had forced his family out of their home on the outskirts of Goražde and they were now living in a small apartment near the hospital. Muharem began bringing the baby to the apartment, where his wife and daughters cared for him during the day, then bringing him back to the hospital at night.

In time, the Muhics gave the baby a name: Alen. Then they stopped bringing him back to the hospital at night. Advija Muhic, Muharem’s wife, recalled her neighbors telling her she was crazy: “They used to say to me, ‘You don’t have enough food to feed yourselves, and you’ve taken in a baby? What are you thinking?’” Even the director of the hospital questioned the Muhics’ choice.

In April 1993, Goražde was declared a “U.N. safe area” and U.N. peacekeepers were deployed to protect humanitarian-aid convoys. The shelling ceased and aid began rolling in. When Alen was five months old, the Red Cross told the Muhic family that it was time to put him up for adoption. A Spanish colonel who had been deployed with the U.N. was interested in adopting him. But the Muhics couldn’t bear the thought of losing Alen, and decided to formally adopt him themselves. The colonel came to their home and met Alen, but didn’t press the matter. “He told us, ‘Don’t worry. I can see how much you love him and I won’t take him away,’” Advija later told me.

So Selma’s abandoned baby legally became Alen Muhic.

I met Alen when he was 3, while first reporting the Newsweek story. Advija, Muharem, and their two daughters doted over the little boy. Theirs was a household full of kindness and joy, and they channeled it into Alen. He was no longer an unwanted baby: He was the cherished son the Muhics always wanted.

Alen was a talkative, friendly toddler, obsessed with airplanes. He had blond hair and big brown eyes. He called Advija and Muharem mama and papa. They hadn’t yet told Alen about the circumstances of his birth; he was still too young. But they had no intention of keeping it a secret. “I don’t know how I’m going to tell him, but I must,” Advija said. If they didn’t tell him, Advija said, she feared somebody else would. Some neighbors referred to Alen as “little Chetnik,” a derogatory term for Serbs. Others casually greeted him as Pero, a common Serb name. Already, Alen knew he was being teased. “I hate it when they call me Pero!” he told me, emphatically. Advija said that occasionally townspeople sneered at her and that she sometimes wished she could run away and live somewhere else.

I found the man Selma accused of raping her at his family home in eastern Bosnia. As we sat outside in his garden drinking slivovitz, a plum brandy, he told me that he knew who Selma was. When I told him that Selma had accused him of raping her and fathering a child, he wrinkled his face in disgust. “Why would I rape her?” he asked dismissively. “She wouldn’t be worth it.” If he had wanted Selma, he said, he could have had her at any time. “I would like her to look me in the eyes and tell me why she says this,” he said.

The story ran in the September 23, 1996, edition of Newsweek. The Muhics said things got more difficult for them after that. The teasing got worse for Alen, and Advija said she had a few unpleasant run-ins at the market. “People used to say things like, ‘When that little Chetnik grows up I hope he kills you,’” Advija said.

I consulted an aid worker who had worked in Goražde and offered to help the Muhics relocate to Sarajevo, where they could be more anonymous. She discouraged it. Unemployment in Bosnia was rampant and Muharem had a job at the hospital in Goražde. She said she would work with Alen’s parents and teachers and get the family the support they needed. As for me, the best thing I could do was leave. “You’ve already done enough,” she said, making it clear that she didn’t approve of the article I had written.

I thought often of Alen over the following years. I wondered what would become of him, when he would learn the truth, and how he would take it. I was racked with guilt for making his life more difficult than it already was. And I thought, too, of Selma. What would become of her? Would she remain trapped in that impoverished, battle-scarred suburb of Sarajevo dreaming of vengeance that would never come?

In time, Bosnia faded from the headlines. I went on to cover other stories—the war in Kosovo, the war on terror, and, for a time, the war-crimes trials in The Hague. By the time it closed down, the U.N. tribunal had indicted 161 suspects, including the Bosnian Serb wartime leaders. Thirty-two of them were convicted for sexual violence. The man accused of raping Selma was not one of them.

As they fretted about how much to tell Alen about his background, Advija and Muharem did what they could to protect their beloved little boy from the taunts and teasing. Advija walked Alen to school and picked him up every day until the second semester of fifth grade. “I wanted to make sure that none of the other kids picked on him,” she said.

By the time Alen turned 10, he didn’t want his mother accompanying him to and from school and insisted on going on his own. On the third day he went alone, he came home in tears. He and another kid got into an argument in the schoolyard and the other kid blurted out that Alen’s parents were not his real parents and that he was a Chetnik bastard who was found in a garbage can. Alen raced home and confronted his parents.

They told him the truth.

After that, Advija said, “We went through hell.” Alen says he always knew he was adopted, and Advija says she never tried to hide it from him. But she recalled how once, when the family was on vacation on the Adriatic Coast, Alen asked her about the scar on her belly. Advija had had a C-section and explained that the scar was from having a baby.

“You lied to me!” Alen screamed at her now. “You said you carried me in your belly!”

Alen sank into despair. He felt betrayed by his biological mother and his adoptive parents, and sickened by the idea that his father was a Chetnik. He had been raised as a Bosnian Muslim. Advija said Alen was angry and would lash out at his parents. He would slam the door and stay in his room and refuse to talk for hours at a time. For a while, he became suicidal.

Not long after Alen learned the truth about his origins, one of his father’s cousins, Šemsudin Gegić, who worked at Sarajevo Television, asked if he could make a documentary about Alen’s story. Alen, who was interested in being an actor, wanted to do it. The Muhics said Gegić suggested the movie could be profitable and that the money could be put away for Alen’s education; they agreed to do it.

A Boy from A War Movie, a 27-minute film that came out in 2004, is a strange synthesis of documentary and fantasy. It begins with 10-year-old Alen wandering onto a film set and asking what the movie is about. When the director tells him, Alen replies that his story is much more interesting. As Alen begins telling his story, a young woman appears on screen, wandering along snow-covered hillsides singing about her search for a “holy child.” The film caused a stir in Bosnia. Until then, there had been very little discussion about rape during the war. It was a taboo topic. Now a little boy was talking about it in a movie. The film made a big splash at the Sarajevo Film Festival, won an award at the Sofia Film Festival, and, unbeknownst to me, was screened at the Tribeca Film Festival, two subway stops from my apartment.

Alen says making that movie—“making my personal life public”—gave him a sense of relief: “As soon as it was done I felt like a burden of shame was lifted from my shoulders. It helped me liberate my identity.”

Apparently, it also made an impression on war-crimes prosecutors.

A Trial

In December 2004, as the U.N. war-crimes tribunal issued its final indictments, it began making preparations for a special tribunal in Sarajevo to prosecute remaining war-crimes suspects. This successor court was to be part of the Bosnian judicial system, but with international judges and oversight. Each judicial panel would have two international judges and one local judge. In time, that ratio would switch to two local judges and one international judge, and eventually to all local judges—the idea being that international involvement would continue only long enough to ensure that Bosnia’s judicial system was up to the task.

A Boy from A War Movie had put Selma’s accused rapist in prosecutors’ crosshairs. They contacted Selma in New York and she told them her story. They contacted her sister, who was still in Bosnia, who did the same. The man was indicted for rape, arrested, and taken into custody. The trial was set to begin before a panel of three judges—a Bosnian and two international judges.

In New York, Selma and her husband began receiving menacing phone calls. One caller threatened to kill their extended families in Bosnia if Selma testified at the trial. But she had been hoping for this moment for years; nothing was going to stop her. When the trial began she returned to Sarajevo to testify.

The accused didn’t show up for the opening of the trial. He sent word from the jail that he was on a hunger strike with other detainees. The trial was postponed a few days, and again he didn’t appear, sending a note to the court saying that he was unavailable due to his “mental and physical exhaustion resulting from the hunger strike.” The court ruled that the trial could proceed without him, and his attorney was ordered to provide him with recordings of the proceedings.

Selma testified from another room as a protected witness, with voice and face distortion. She was disappointed that she wasn’t able to face her assailant in the courtroom. Her sister testified as a protected witness as well. She told the court that she saw the man when he came for her sister, and that Selma returned home in a ripped dress, battered, bruised, and crying. A psychiatrist testified as to both the defendant’s and Selma’s states of mind.

A forensic team went to Goražde to collect saliva and hair samples from Alen, who was now a teenager. The trial was covered by the Bosnian media, and the Muhics heard on the evening news that the DNA results confirmed that the accused was the father of the child in question. “It’s true, I really was created by a Chetnik,” Alen sobbed that night. He again retreated to his room and wouldn’t come out for hours at a time.

And then two Bosnian Muslim men testified—protected witnesses C and D—and what they told the court complicated what had looked like an open-and-shut case. They claimed that the defendant and Selma were involved in a consensual relationship before the war.

Witness C said that the defendant confided in him that he was having an affair with a Bosnian Muslim. When rumors about the affair began to spread at the mine where the defendent worked, witness C said he advised his friend to end it. Witness D confirmed the relationship and added that the accused’s family had helped many Bosnian Muslim refugees get safely out of the area during the war.

The defense lawyer argued that the DNA test was not proof of rape, only of a sexual relationship. The defendant acknowledged paternity and told the court that he was willing to meet and care for his son.

To this day, Selma denies that she was ever involved romantically with him. Speculation among Bosnians who followed the trial is that witnesses C and D were not telling the truth. Whatever the case, the judges deemed the testimony credible, writing that it “unequivocally confirmed the fact that the Accused and witness A were having an extra-marital relationship before the war.”

But the judges also concluded that Selma and her sister’s testimony was credible. They noted that there were some inconsistencies, but said they were “utterly consistent and correspondent in their essential and important elements, and … do not raise suspicion in relation to the authenticity and credibility of the accounts.”

In the end, the judges ruled that “the state of war changed the nature of the previously mutually accepted existing relationship.” They said that since the accused was a soldier and Selma was a civilian from the opposing side, the circumstances were so coercive that she was “not in a position to give true consent.” They deemed the pre-war relationship a mitigating factor, along with the fact that the defendant professed a desire to care for Alen, and sentenced him to five years and six months in prison, with credit given for time served. They also said he would be prohibited from initiating contact with Alen, but should Alen want to have a relationship with him, he needed to make himself available.

For the first time in years, Selma told me, she felt a sense of peace.

But the man appealed. By the time the appeal was heard, the ratio of international to local judges had changed. It was now two local judges and one international, an American. They did not call back any of the witnesses who had testified previously. It was a new set of judges looking at the same evidence, plus testimony from the attending doctor at the Goražde hospital where Selma gave birth.

The appellate judges said the inconsistencies in Selma and her sister’s testimonies called into question their integrity and truthfulness. They accepted the testimony from the witnesses who said Selma and the man had had a consensual relationship, and said the fact that Selma didn’t tell the court about it undermined her credibility.

They also said that Selma exhibited a “lack of logic in her description of the event,” pointing out that she told the court that the accused once asked her if she could be pregnant. The judges apparently interpreted this as him showing concern for Selma. “Such a behavior by which the rapist brings the attention of the pregnancy problem is not a usual or logical behavior of the person charged with rape committed within the crime in question, raising an additional suspicion whether it was really an involuntary relationship,” they wrote.

They questioned why in her initial meeting with war-crimes investigators, Selma said she was raped in her attacker’s apartment, but only later said she was raped on multiple occasions in his apartment.

Finally, they questioned why, if it was really rape, Selma did not explain this and ask for an abortion rather than hiding her pregnancy once she arrived in Goražde. The ruling made no mention of the possibility of trauma, shame, or lack of abortion access in a besieged enclave whose hospital lacked the most basic supplies and was overwhelmed with war casualties.

Selma’s alleged assailant was acquitted of all charges.

The verdict shattered Selma. For years, she dreamed of justice, of her rapist being held to account for what he had done. She had built a new life in the United States and still went back to Bosnia to testify all those years later, only to be told that what happened to her was not rape. “I don’t care if he only got one day in prison, I just wanted him pronounced guilty,” Selma told me when I visited her in New York. “If I had known that this was going to happen, I would have killed myself.”

When Alen turned 21, he decided he wanted to meet his biological parents. What really happened between the two of them? Why did his mother leave him? And did his father really want to have a relationship with him? So in 2014, when Šemsudin Gegić proposed making a second film, about the search for his parents, Alen agreed.

Gegić arranged a meeting with Alen’s biological father. But when Alen and the film crew showed up, a man who was not Alen’s father greeted them and announced that the meeting would not happen. He said that the man in question was not Alen’s father, that he had no relation to Alen.

Through some detective work, Gegić contacted Selma in New York. He said Selma initially agreed to meet her son and cooperate in the making of the film but then changed her mind. I would later learn that Selma’s husband opposed it. Their children still did not know that Selma had been raped and certainly not that they had a half-brother in Bosnia. Whether Selma’s husband thought meeting Alen would would upset her, or whether he was concerned about his children finding out about their mother’s past, I don’t know. But in the end, Selma declined.

At that point, Alen abandoned his search. Gegić wound up making a movie anyway. An Invisible Child’s Trap came out in 2015. It was another strange synthesis of documentary and reenactment. There was the real Alen, and then there was Alen’s alter-ego, played by an actor. And again, there was an actress portraying Selma, this time clad in a red silk dress, clinging to the side of a bridge over the Drina. It premiered in Goražde, was attended by town officials, and received a standing ovation.

But if Gegić’s movie did not capture Alen meeting his biological parents, it laid the groundwork for that very thing. Sometime in 2016, Alen received a call from a Muslim cleric saying that Alen’s biological father was home. Alen and a friend drove to the house, which he knew from having gone there with the film crew. A middle-aged man opened the door. “It was like looking at myself 30 years in the future,” Alen told me. “It was like copy, paste.”

The two talked for an hour. Alen said the man claimed to know who Alen was from the movie and the media coverage around it, but that he never knew Selma and that he never committed any crime. Alen said he also claimed that he had been set up and that the DNA test was rigged. “He actually tried to make himself the victim,” Alen said.

When Alen challenged him on it, his father got angry and told him to leave. Alen said he felt no personal affinity for the man and said he never wanted to see him again. “He’s my biological father on paper, but that’s all he is,” he said. “I would not even call him a person. For what he’s done, I would call him a monster.”

In New York, Selma read an article about the premiere of the movie in Goražde and was apparently so moved that she called Gegić and said she wanted to meet Alen after all. Two years would pass before it would finally happen. In 2017, Alen received a phone call. It was Selma. She was in Sarajevo and wanted to meet him. “I’ll never forget that call,” Alen said. “It was my first direct contact with her. I didn’t know if I felt happiness, joy, or sadness. I was full of adrenaline.”

By then, Alen was working as a nurse at the hospital where he was born. His wife, who is also a nurse at the hospital, was pregnant and about to give birth. Alen was slammed at work, but he dropped everything and drove the two hours to Sarajevo. He said his heart was racing as he approached the house where she was staying. He went inside and found Selma sitting on the sofa, in tears.

Alen said Selma told him that she had wanted to meet him earlier, but didn’t have the nerve. Once, when visiting her family in Bosnia, she said, she went to Goražde and waited outside Alen’s school, hoping to catch a glimpse of him.

Alen said he didn’t know what to expect from meeting Selma, but one thing was clear: Whereas he was once angry at her for leaving him at the hospital and not wanting to meet him, after meeting her, his anger evaporated. “I don’t blame her for anything after what she went through,” he says.

Alen returned to Goražde that night in tears. “He hugged me,” Advija said. “And thanked me for being his mother.”

How Things Are

Alen has come to terms with who he is and how he came into this world. In addition to being a nurse, a husband, and a father, for a time he was the co-chair of an organization called Forgotten Children of War, which works to lift the stigma of rape and children born of rape. Alen and the other members have asked the Bosnian government to recognize them as war victims so they can qualify for certain kinds of state benefits, and to change official government forms so that people are no longer required to provide the name of their father when applying for financial aid or requesting a driver’s license.

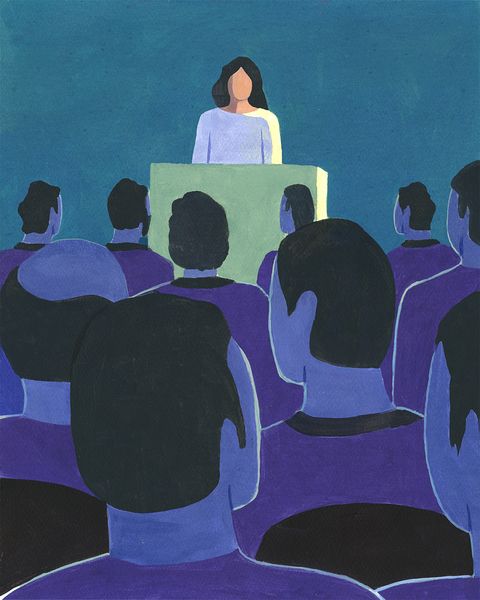

In October 2019, he traveled to New York to speak at a U.N. conference on sexual violence in conflict. Poised and dressed in a dark suit, he told the assembly: “My mother left me two days after my birth and went on with her life. My biological father is a man convicted of wartime rape. I was adopted by a janitor who was working at the hospital where I was born. … Today I am happy to be able to speak freely and proudly about myself and my family without a speck of shame.” When he finished speaking, the room erupted with applause.

The day before his speech, we met in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and spent an afternoon walking and talking in Central Park. I had feared that Alen would be a traumatized soul, like so many young men who came of age in the post-war deprivation of Bosnia. I also feared he might resent my part in outing him as a child of an alleged rapist. The young man I met was gentle, charismatic, and kind. He said that there was a time when he was angry and consumed with revenge, but that he “consciously decided to lead a life of love.” He said the fact that he was forced to confront the truth and process it was his saving grace and he thanked me for my part in it, an outcome I could have never imagined. He said meeting his biological parents gave him some closure, but he would still like to meet his half-brothers.

That is unlikely to happen anytime soon. When I asked during my visit with Selma what it was like for her to meet Alen, her husband, who was translating for us, said that they never met. Selma apparently had not told him that she met Alen. When I mentioned that Alen would like to meet his half-brothers, Selma’s husband was unequivocal. “I don’t accept that,” he said. His rejection of the idea is not ill-intentioned. He is a kind, gentle man who has shown extraordinary patience and love in caring for Selma for all of these years but he doesn’t want his children to know what their mother suffered or that they have a half-brother in Bosnia.

Since the conviction in Selma’s case was overturned on appeal, much has come to light on the tortured logic of the decision that acquitted him as well as the questionable ethics of some of the key players in the case. Several years after the verdict, the chief judge on the appellate panel was indicted for accepting a bribe in another case. She was convicted and sentenced to two and a half years in prison. Her appeal is still pending. The lawyer who represented Selma’s alleged rapist in his appeal was also indicted—for fraud and money laundering.

No evidence has emerged suggesting that either the chief judge or the defense counsel were involved in bribery or fraud in Selma’s case, but the indictments do raise serious questions not only about their character but about the integrity of the Bosnian justice system.

As for the question of a previous consensual relationship, it turns out that Bosnian law prohibits defendants from introducing evidence of consent in war crimes cases. The law presumes what the trial judges ruled: that the coercive circumstances present during an armed conflict presume non-consent. A strict reading of the law would suggest that testimony that Selma and the man she says raped her were in a sexual relationship before the war should not have been permitted into evidence.

I spoke with the American judge on the panel that acquitted Selma’s alleged rapist. He said he could not comment on specific cases, but noted that the Bosnian war crimes court did not permit dissenting opinions. He also said that in this case, the court applied the legal principle of in dubio pro reo, which means: When in doubt, rule for the accused.

I showed the decision to Joanne Archambault, a recognized expert on sexual assault. She is a former sex crimes investigator at the San Diego Police Department who now heads an organization called End Violence Against Women International, which trains police, judges, and prosecutors on sexual assault. She said the verdict rested on the judges’ flawed notion that a victim’s testimony should “not raise any suspicion as to its exactness and truthfulness.” “Witnesses are not perfect,” she said. “There will always be inconsistencies. If five people interview the same victim, they will produce five different stories depending on their professional roles, training, and skills. You can read the interviews and it will sound like they contacted five different victims. Half the time, it’s the interviewer, often unintentionally, creating the inconsistencies. That doesn’t mean the vicitim’s account isn’t credible.” In this case, she said, the inconsistencies were minor.

That the judges would bring up the fact that Selma went to her attacker’s apartment multiple times and that she tried to hide her pregnancy as evidence that the relationship was consensual was shocking, Archambault said. “It’s so easy to write off rape as an affair gone wrong. I see it all of time in the United States. Judges grab on to a little bit of doubt and make assumptions. That they would subscribe to the rape myth is not a surprise,” she said. “But that they would dismiss a woman’s survival instincts? I’ve never seen anything like it.”

The war-crimes chamber, which is heavily subsidized by the European Union, is supposed to complete its cases and shut its doors by 2023. Its success in convicting sexual assault is impressive by most standards. Of the 45 cases the court heard between 2005 and 2013, 73 percent resulted in conviction, and 27 percent in acquittal. (That is a higher conviction rate than in the U.S., where about 56 percent of rape prosecutions wind up with convictions.) But the case of Selma’s attacker calls that legacy into question, and I can’t help but wonder if the panel of judges might have ruled differently if the trial had taken place today in the wake of the global #MeToo movement.

In a new book about wartime rape, Our Bodies, Their Battlefields, Christina Lamb, a longtime correspondent for Britain’s Sunday Times, recounts a war-crimes case at the Rwanda tribunal where judges laughed when defense lawyers expressed doubt that a woman could have been raped 16 times because “she had not bathed and smelled.” It’s hard to imagine such overt dismissal of women’s suffering being tolerated in a courtroom today.

In 2018, as the global reckoning over sexual violence was underway, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to two campaigners against the use of rape as a weapon of war. One of them was Nadia Murad, a Yazidi woman who, along with thousands of others, was abducted and raped by ISIS militants in 2014. Most of the women refused to be named, but Murad went public and went on to start Nadia’s Initiative, a non-profit organization that advocates for wartime survivors of sexual violence.

In 2020, her organization teamed up with the U.K. Foreign & Commonwealth Office and the Institute for International Criminal Investigations to establish a universal code of conduct for investigators collecting evidence from victims of conflict-related sexual violence. Known as the Murad Code, it includes input from survivors on how to document sexual assault. Among the recommendations is to avoid repeated and unnecessary re-interviewing of victims, in part because it is traumatizing, but also because doing so increases the possibility of creating contradictions—the likes of which undermined Selma’s credibility in the judges’ eyes.

Prosecuting rape as a war crime has never been easy. Despite the precedent set by the Yugoslav and Rwanda tribunals, there has been little international will to hold accountable militants from ISIS. But pressure is mounting. In December 2020, the chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court announced that there was enough evidence to open a full-scale investigation into war crimes, including rape, conducted by the Nigerian jihadist terrorist organization Boko Haram, which has abducted thousands of young women and forced them into slavery.

It will take sustained pressure to bring about prosecutions for mass rape, whether in a U.N. tribunal, a hybrid court, or the International Criminal Court. But should it happen, it will rely on the precedent set by the effort to prosecute rape as a war crime in the former Yugolsavia—and the lessons learned as well.

When I got in touch with Selma after all of these years, I had wondered if something might be done about her case—whether she could appeal or petition for some kind of an extraordinary legal remedy. After all, Selma’s alleged assailant was acquitted because the appellate judges didn’t find Selma’s testimony credible—in dubio pro reo. They ruled that what transpired between him and Selma was not rape, but a consensual relationship. But what about the accused’s subsequent claim that he was never involved with Selma, that the DNA test was rigged, and that he is not Alen’s father? Whose testimony is more credible? A soldier who based his entire legal argument on having had a consensual relationship with Selma, acknowledged paternity, and said he was willing to have a relationship with his son, then denied all of it after he was released? Or a woman who said she was raped, gave birth to a child that she abandoned, then returned to Bosnia to testify years later despite having started a new life in the United States?

Unfortunately for Selma’s sake, there appears to be no legal remedy. According to Bosnian law, a trial cannot be reopened to the detriment of the accused. The state might have been able to appeal to the Bosnian Constitutional Court, but it would have had to do so within 60 days of the verdict’s rendering. Similarly, the state could have appealed to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, but it would have had to do so within six months of the verdict.

A week after I visited Selma, her husband called me. He said it was a mistake for Selma to have talked to me. He said that for the past six years, Selma had been stable, but that my visit had upset her. He said she thought that I could change something. “But Stacy, let’s be honest, you can’t change anything,” he said. “Please, tell her nothing will change. Tell her she needs to forget about this case. Tell her she has two beautiful children. She is safe. She needs to forget about this.”

He said I was welcome to come upstate and visit anytime, but that I should never again mention one word about the case. A few days later, he sent me a message saying she was feeling better but that I should not waste my time coming to visit. “Selma is not ready to meet anybody. She says we have to close this case. We wish the best for you and your family.” I tried to reach Selma a few times since then. The last time I called, her husband answered the phone. I asked how she was. He told me that she was fine, and hung up.

While I was in Bosnia researching Selma’s case, I went to visit Alen and his adoptive parents in Goražde. Days before I arrived, a woman gave birth to an unwanted child at the hospital. Alen and his wife volunteered to adopt the baby. In the end, the birth mother’s parents came forward to care for the child. Sitting in his apartment overlooking the Drina as his 3-year-old son played with a helicopter, Alen said he was happy the baby found a home, but that he would have loved to have expanded his family that way. He again expressed a desire to get to know his birth mother and meet his half-brothers in New York. “If it were up to me, we would all sit down together,” he said.

I can’t help but wonder what that might be like for Selma. Imagine if she could inhabit a world where she didn’t need to hide what had happened from her American children. What if she, like Alen, could feel the sense of relief that comes with lifting the burden of shame? What if she could feel heard, and understood, face the truth instead of trying to hide it? Imagine if her American children could support her instead of being left in the dark to wonder what awful thing happened to their mother during the war. Maybe then, she could find the peace that has so improbably blessed the child she left behind in Bosnia.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center, as well as a grant from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.

Illustrations by Holly Stapleton