An embattled Warren faces a mayoral challenge from Evans | News

Mayor Lovely Warren stood at the podium outside her office at City Hall facing what would have been a circular firing squad of reporters had she given them a chance to pull the trigger. There were plenty of questions.

Her husband, Timothy Granison, had been arraigned on drug and weapons charges earlier in the day. Prosecutors alleged he was a player in a cocaine ring and police claimed to have found drugs on him and an unregistered handgun and a semi-automatic rifle in the Woodman Park house he shares with Warren and their 10-year-old daughter.

But Warren did what she has done so adeptly before: defiantly played the victim and turned the tables on the media by urging them to take their questions elsewhere. She framed her husband’s arrest as politically and racially-motivated, and urged reporters to ask why law enforcement would move in on her husband just a month before the June primary.

“We need to ask ourselves, if this is not about politics, why is Tim’s next court date June 21, the day before Primary Day?” she said. “Now that’s quite the coincidence. Now when you figure out those answers to those questions, come find because I’ll be working.”

Then she turned around and walked through the wooden door to her office, refusing to take questions.

READ MORE: Mayor Warren delivers defiant address after husband’s arrest

The reporters there had the answer to her question. Her husband’s lawyer had asked for a 30-day adjournment between Granison’s arraignment and his next court date and the judge granted his request, scheduling the next appearance for June 21.

Now, among the questions that reporters and political observers and countless other Rochester area residents with a stake in who helms City Hall had, was how much longer Warren may be working behind that wooden door.

Just a day before police had raided her home, there was no such question. Despite her last year in office being whipsawed by crises, that she would waltz to a third term by winning the Democratic primary was a foregone conclusion to virtually everyone who follows local politics.

Even allies of Warren’s primary opponent, City Councilmember Malik Evans, acknowledged that his bid to unseat her was an uphill battle. His campaign, defined by the motto “we can do better,” had registered barely a blip on the political Richter scale. It had been four months since Evans announced his candidacy, and the only proposal he had released was a youth jobs initiative to curb violence.

“She has served two terms as mayor, the city knows her well, she is loved and deeply respected by large numbers of voters in the city, and she has proven resilient and popular across two campaigns so far,” Gerald Gamm, a professor of political science at the University of Rochester and longtime friend and supporter of Evans, said of Warren before her husband’s arrest.

“Lovely Warren is not one to underestimate,” Gamm said. “She is a talented and skilled political leader.”

But her husband’s arrest has changed his perception.

“I think there will be a critical mass of voters, who have voted for her in the past that will say, ‘Enough is enough,’” Gamm said later.

Political observers are viewing the arrest of Warren’s husband as a potentially game-changing event.

Timothy Kneeland, a political science professor at Nazareth College, said a few days prior to the arrest that the race was heavily leaning in Warren’s favor.

After the arrest, he thought the scandal could doom her, even if she manages to win the Democratic primary. Evans has committed to see the race through November as a candidate on the Working Families Party line regardless of the outcome of the Democratic primary.

“Over time, details are going to come out, and those details may ultimately exonerate her,” Kneeland said. “But when you put all of these pieces together, and all of the things voters have seen in the past year, this makes it a far more difficult race for her.”

In late May, WROC-TV and Emerson College released a poll of 1,000 Rochester voters who were surveyed in the two days following news of her husband’s arrest. The poll reportedly showed Evans leading Warren by 10 points. Among likely Democratic primary voters, his lead narrowed to one point, 46 percent to 45 percent. The poll had a margin of error of 3.8 percent.

WARREN IS DOWN. BUT IS SHE OUT?

Throughout her two terms as mayor, Warren has been a polarizing figure.

She has high-profile detractors, but also fiercely-dedicated allies in the Democratic Party and among constituents of faith, and an organization that has proven its ability to get them to get to the polls. Her machine rose to prominence in 2013 when she stunned Democrats by ousting Mayor Tom Richards in the primary.

The Saturday following her husband’s arraignment, Warren took to the microphone on the steps of City Hall for a Pentecost Sunday celebration and belted out a soulful rendition of the Miami Mass Choir’s “It’s For Me” before breaking into tears and being embraced by a small crowd of onlookers.

“What God has for me, it is for me,” she sang.

The past year has been particularly turbulent for the mayor, personally and professionally.

The late Assemblymember David Gantt, her political mentor and a man she has said was like a father to her, died in July. A few months later, she lost her mother to complications from COVID-19. In between, word of Daniel Prude’s fatal arrest was released, sparking weeks of civil unrest, dismantling of the Rochester Police Department’s entire command staff, and widespread calls for Warren to step down.

A City Council-commissioned investigation of a cover up at City Hall faulted Warren for keeping critical details of his death secret for months and for lying to the public about when she knew — a finding that Evans said “did little to restore confidence” in city government. In the meantime, Warren was indicted on felony campaign finance charges.

Through it all, Warren has remained defiant and deflective.

Perhaps no greater example exists than the five-minute speech Warren gave to reporters the day of her husband’s arraignment, in which she suggested her indictment and her husband’s arrest were evidence of District Attorney Sandra Doorley’s attempting to “break” her as retribution for Warren’s support of Doorley’s opponent in the 2019 District Attorney race.

Doorley has denied the criminal cases against Warren and her husband are political and has taken pains to outline to the public why. In the matter of the campaign finance allegations, Doorley has said, those charges stemmed from an investigation by the state Board of Elections. As for Warren’s husband, Doorley has said that he wasn’t an initial target of the sting that resulted in his arrest. It was only about three months ago, she said, that conversations captured on police wiretaps in connection with a broad investigation revealed that he played a role.

READ MORE: Mayor Warren’s husband pleads not guilty to drug and weapons charges

Warren’s finger-pointing even had her long-time ally, former Mayor Bill Johnson, shaking his head and worrying for her political future.

“This just was a body blow,” Johnson told a television news station after the arrest.

“Somebody put those guns in that house, knowing that there was a 10-year-old child who lives in that house. You can’t be pointing fingers and say, you know, ‘Who committed a conspiracy against me?’ You’ve got to own up to the fact that you need to know what’s going on in your own house.”

Warren doubled-down on her conspiracy theories, saying in her speech that her troubles have taught her that not much has changed since the 1860s and 1950s, implying that race has been a motivating factor in her problems.

Indeed, her campaign invoked race in response to Evans launching his mayoral run in January, releasing a statement that suggested Evans, a Black man, was following in a long line of Black men who look to oust Black women from power.

“We’ve prepared for this moment,” the statement read. “All over the country unfortunately it’s been our brothers that have been first in line to take on sisters. The powers-that-be playbook hasn’t changed since the days of slavery.”

The deflections are not lost on her opponent.

“As a leader, you can’t claim all of the good stuff that’s happening and then blame and deflect all the bad stuff that’s happening on other people,” Evans said of Warren the day after her husband was arraigned.

RUNNING ON HER RECORD

Despite her tumultuous last year in office, Warren has said she intends to run on her record and can point to tangible accomplishments during her tenure.

Although the filling in of the Inner Loop East was initiated before her time in office, the work happened on her watch and the result has been an impressive array of private-sector residential and retail development unlike anything the city has seen in recent memory. Her administration has also invested heavily in infrastructure, specifically projects that have beautified long-neglected parcels along the Genesee River, with the popular Roc City Skatepark being the most prominent example.

“In every corner of the city we have new buildings going up, we haven’t had this much investment in our city in over a decade,” Warren said during an interview. “When you put it all together, it is extraordinary the work me and my administration have been able to accomplish by working together, despite all of the stuff people want to focus on.”

Warren spoke with CITY by phone a day after her defiant speech following her husband’s arraignment. She tried to keep the focus on her accomplishments as mayor — enacting financial-empowerment initiatives for residents, keeping the city afloat through the pandemic, restructuring the Police Department, and initiating the city’s Person-in-Crisis Team that assists police in responding to mental distress calls, an issue that took on more prominence in the wake of Prude’s death.

[pdf-1]

She recently outlined her vision for an “equity and recovery agenda,” which stresses directing tax dollars from the legalization of marijuana into home ownership programs, and proposed a budget for the upcoming fiscal year that was responsive in many respects to demands of the social and racial justice movement that is gaining traction in the mainstream.

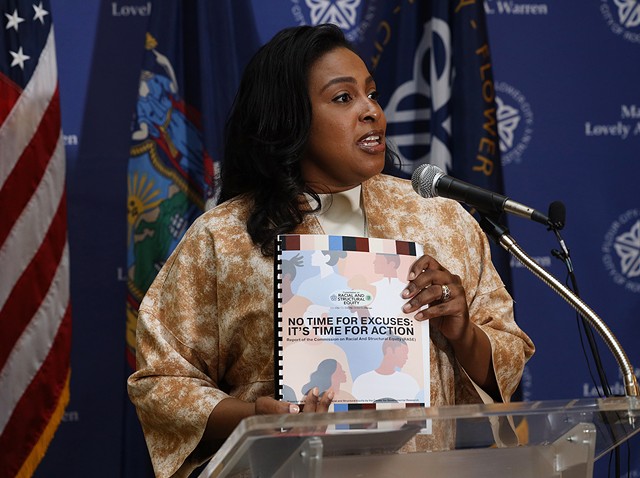

Warren proposed directing $1 million toward implementing recommendations of the city-county Commission on Racial and Structural Equity, trimming funding to the Rochester Police Department by about 5 percent, and meeting the request of the Police Accountability Board for $5 million in funding to hire teams of investigators.

“The major hallmark of our time here has been really doing the work for the citizens of Rochester,” Warren said. “. . . Hopefully, the work we’ve done over the last seven years, they can see it.”

Warren said she doesn’t believe her husband’s arrest will have an impact on the upcoming primary, in part because of her administration’s accomplishments and in part because she’s not been implicated in his arrest.

She has distanced herself from her husband by saying that they have been legally separated for years but live together to co-parent their daughter. There are no public records of legal separations, unlike divorces, which are filed in courts of law.

“It’s about pointing to the work,” Warren said. “I think that there’s a lot of people that have faith in the work that we’ve done.

“Do you believe that the Department of Neighborhood and Business Development getting out hundreds of loans to businesses was the right thing to do? We did that. Do you believe that the Department of Neighborhood and Business Development helping hundreds of people stay in their home was the right thing to do? We did that.”

EVANS MAKES HIS MOVE

While Warren is simultaneously campaigning and doing damage control, Evans has largely refrained from seizing on the mayor’s latest crisis, preferring instead to run on his ideas.

Asked by a reporter during a news conference he staged a day after Warren’s husband was arraigned whether he thought she could still govern, Evans quipped, “You have to ask her that. That’s like asking a person with one hand whether they can clap.”

He was there to present his plan to address the surge of gun violence in the city, which would include the creation of a gun czar, a civilian position that would report to the mayor. The closest he came to invoking Warren’s turmoil was to say that her succession of scandals were distracting from important challenges.

“The focus needs to be put back on the citizens of Rochester,” Evans said. “Enough of the drama.”

A week earlier, Evans sat down in a conference room at his campaign headquarters overlooking the newly-sodded Parcel 5 for a wide-ranging interview with CITY. There, he laid out his ideas to unite Rochester.

“We got to do the hard work of getting people in a room together to say, ‘Okay, how can we move forward in order to get things done, so that we can have the trust of the citizens,’” Evans said. “That’s what I’m committed to, and that’s what my record has been.”

Evans is running on a platform of being a “bridge builder” and has emphasized bringing more transparency to City Hall.

In most political races, such a statement would seem like a platitude. But the Warren administration has been dinged repeatedly for filtering the information that flows from City Hall. Prude’s death and the failure of police and city officials to inform the public about it is one example, but another is the sometimes slow turnaround time for records requests made under the state Freedom of Information Law (FOIL).

Evans has dubbed his policy package a “compact with the community,” a series of commitments in five areas — youth development, public safety, economic empowerment, neighborhood development, and trust and transparency.

“You got to look at this from a holistic standpoint,” Evans said.

“Holistic” is a word that Evans uses often. To him, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution to Rochester’s problems. The answer, he said, lies in community-level initiatives that touch on the nuances of neighborhoods and issues.

In regard to public safety, for example, Evans wants to rethink the role of police, and is supportive of adding more resources for dealing with mental health and substance abuse issues beyond police officers.

“What do we want policing to be? We don’t want police officers to be mental health counselors,” Evans said. “So how do we ensure that we build a system where we have large-scale mental health services at both the city and county level. So if a 9-year-old girl is having problems with her family, it’s not the police that are responding.”

A persistent problem for Evans, however, has been differentiating himself from the mayor. The pillars of his platform are areas that Warren has at least attempted to address.

When Evans makes a case for building the city’s economy by supporting small businesses rather than through large-scale development, the mayor can point to her crowdfunding microloan program, for which the U.S. Conference of Mayors recognized her with a Small Business Advocate Award in 2017.

The political careers of Evans, 41, and Warren, 43, have in many ways paralleled each other.

Evans joined the Rochester Board of Education in 2003, when he became the youngest person ever elected to the board. He would eventually become its president. In 2017, he was elected as an at-large member of City Council, where he now chairs the Finance Committee.

He was in his second term on the school board when Warren was elected to City Council in 2007. Three years later, she was named the youngest Council president in history.

What Evans has to his advantage, though, political observers say, is the seemingly ceaseless drama of the Warren administration and the toll it has taken on the psyche of residents.

Whether his message of “building bridges” is enough to harness it is a matter for voters, specifically enrolled Democrats, whose votes in the primary could solidify the outcome of the race. Evans, whose backing by the Working Families Party has ensured him a place on the November ballot, has said he will campaign through the general election regardless of the primary outcome.

“That’s a lot for a city to recover from…I hope that people will say, ‘You know what, we got Malik’s back, he can’t do this by himself,’” Evans said. “And I won’t try. That’s why this building bridges thing is not just a crazy campaign slogan, that’s the truth.

“If you’re going to dig yourself out of this hole, you better be able to build some bridges.”

Gino Fanelli is a CITY staff writer. He can be reached at (585) 775-9692 or [email protected].

Jeremy Moule is CITY’s news editor. He can be reached at [email protected].