Homeless Oaklanders were tired of the housing crisis. So they built a ‘miracle’ village | Oakland

Tucked under a highway overpass in West Oakland, just beyond a graveyard of charred cars and dumped debris, lies an unexpected refuge.

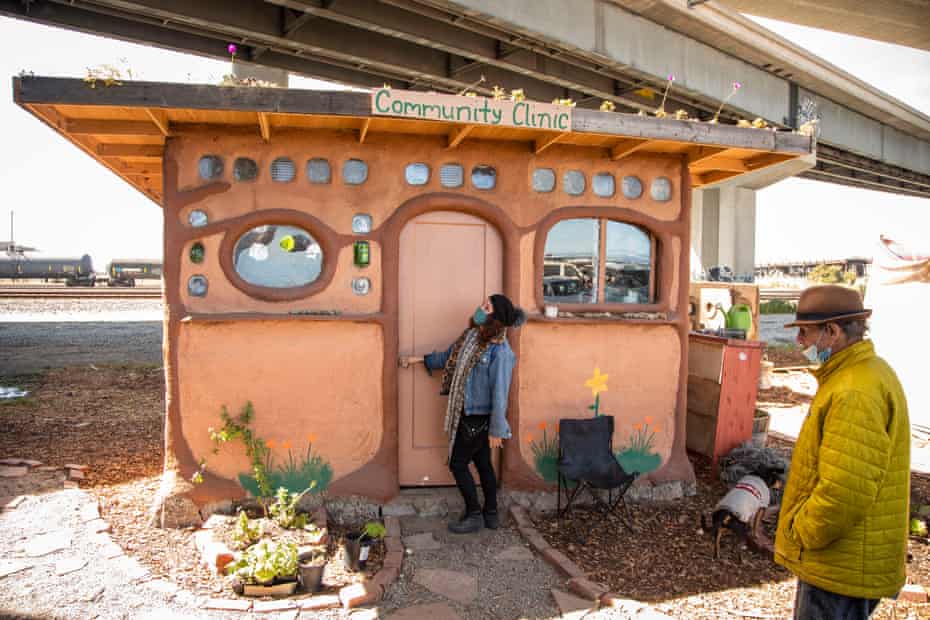

There’s a collection of beautiful, small structures built from foraged materials. There’s a hot shower, a fully stocked kitchen and health clinic. There’s a free “store” offering donated items including clothes and books, and a composting toilet. There are stone and gravel paths lined with flowers and vegetable gardens. There’s even an outdoor pizza oven.

The so-called “Cob on Wood” center has arisen in recent months to provide amenities for those living in a nearby homeless encampment, one of the largest in the city. But most importantly, it’s fostering a sense of community and dignity, according to the unhoused and housed residents who came together to build it. They hope their innovative approach will lead to big changes in how the city addresses its growing homeless population.

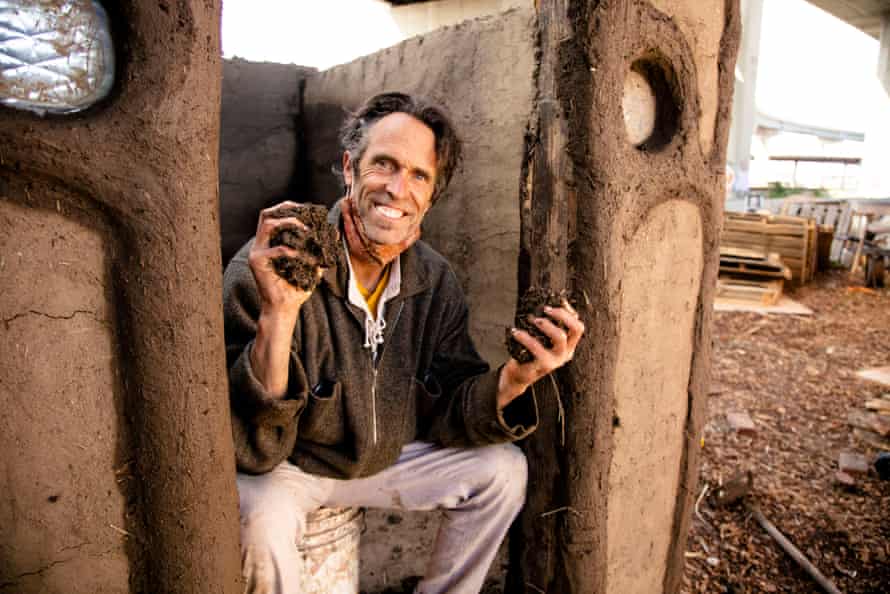

“It is about uniting everybody,” says Dmitri Schusterman, a nearby resident who also serves as the Director of Innovation for Artists Building Communities, one of the organizations that helped build the center at the end of last year. Cob on Wood was brought to life with help from local advocacy arts and food groups who teamed up with Miguel “Migz” Elliott, an expert in the ancient technique of making cob structures. Together with teams of volunteers and residents, they built each component by hand.

Now, roughly five months since they broke ground, a community has coalesced around the space that not only hosts events and workshops but also offers food, hygiene and skill-sharing to the estimated 300 people who live in nearby encampments.

“It is working,” Schusterman says, smiling broadly. “This is the vision we had and it is working like a miracle.”

Tackling a pair of crises

Cob on Wood was born of parallel crises – Oakland’s rising rate of homelessness and the Covid pandemic.

The city is home to more than 4,000 unhoused people, a figure that has jumped 86% over a four-year period, according to a 2019 report. Homelessness disproportionally affects Black Oaklanders, who make up 24% of the general population but 70% of the unhoused population.

Xochitl Bernadette Moreno and Ashel Seasunz Eldridge, co-founders of Essential Food and Medicine, one of the organizations behind Cob on Wood, distributed food and hygiene products to those who couldn’t “shelter in place” during California’s lockdowns. That’s when they learned about just how dire the situation had become.

“[Covid] exposed those pre-existing cracks in the infrastructure of how we take care of our people, our communities, our neighbors,” Eldridge says.

Moreno adds: “Knowing that the issues people in these communities face around hunger and access to water, access to places to cook – these issues existed before the pandemic and they will continue to exist after the pandemic.”

There are at least 140 homeless encampments in Oakland, according to a recent city audit, which found the city had mismanaged its response to the crisis. Building on findings from the United Nations general assembly, which, after visiting the Bay Area in 2018, reported that treatment of the unhoused was “cruel and inhumane”, Oakland’s audit reported that many unhealthy and unsafe conditions have persisted, including a lack of access to clean water, sanitation, and health services.

City officials have tried to address the growing issues with new programs, including the “tuff shed” project that provides clusters of small structures as temporary housing solutions and so-called “Safe RV Parking” sites that include access to electric hookups, portable toilets and security.

But critics – who include some of the unhoused participants – say the programs are plagued with safety issues and do little to address underlying causes of housing instability. Some have also expressed concerns that the programs have given the city more political leeway to crack down on encampments and increase sweeps, an often traumatic process for unhoused people who can end up losing their few belongings.

“People are not only being evicted from homes they once had, but then they are being evicted from the homes that they create – communities they’ve built for themselves when they had nowhere else to go,” Moreno says.

After growing frustrated with the city’s interventions, several other communities have attempted to create their own solutions, including a group of women who started a safe encampment in vacant lots, and an advocacy organization called the Village, which has built tiny homes on empty areas of public land across the city.

Cob on Wood organizers are also hoping to empower unhoused residents to solve the problems they think the city hasn’t adequately addressed – from fire prevention to sanitation access – while organizing to collectively engage with officials and limit the sense of “otherness” and disenfranchisement which residents say is an all-too-common side-effect of homelessness.

They broke ground in December. Clearing needles and trash from an area near Wood Street – a half-mile area lined with makeshift structures, RVs and tents – a crew of volunteers and camp residents under Elliott’s guidance used pallets to frame the structures. They were insulated with scavenged materials before being coated in “cob”, a mixture made from organic materials including sand, subsoil, water and straw.

Each structure is lined with a “living roof” – featuring a garden – that creates an attractive aesthetic while insulating the inside from the abrasive city sounds and the elements.

“There are cob structures that were built 700 years ago that are still being lived in,” Elliott says. He hopes to prove that “cobins”, as he calls them, could serve as a quick and affordable addition to other encampments, to offer shelter and house other services.

“I am trying to demonstrate a structure that can be built for as cheaply as possible, as naturally as possible, as beautifully as possible and as movable as possible,” he says. “They can have a lock on the door, some shelves on the wall, a little garden on the roof, and the people living in them can actually help build them.”

Cob on Wood organizers also plan to host educational opportunities, including nutrition and cooking classes, skill-shares and career development. “We believe that this place can serve as a model.” Moreno says. “That this city and other cities can adopt to be able to replicate these ideas and create workforce development programs.”

‘Making us feel good about ourselves again’

So far, the city has expressed support for the project. Or at least interest.

Carroll Fife, a city council member, has been visiting the encampment and meeting with residents. And while Cob on Wood was built without a permit on land belonging to the state’s transport agency, Caltrans, the agency says it has no immediate plans to remove the structures – though it hasn’t ruled out eventually doing so.

Residents and organizers are still concerned. They have experienced sweeps conducted by the city and Caltrans before, and there are rumors that clean-up crews could be deployed to clear the area in the coming weeks.

But they hope that this time, things will be different. The group has already raised more than $24,000 through GoFundMe, and there are plans in the works to expand Cob on Wood. Elliott would like to build a chicken coop to house egg-laying hens, a pond full of water-loving plants to collect the runoff from the shower, and a gray water system that will recycle water so that a washer and dryer can be installed.

They’d also like to build residential “cobins” that people could live in long term – that is, if the community is able to stay. Those involved say the project has already had a positive impact – and are determined to build a future for it.

Leajay Harper, who serves as the kitchen manager, is among them. Born and raised in Oakland, Harper lost her housing after losing her job at a non-profit during the 2008 financial crisis. She sent her children, now 14 and 18, to live with her mother, hoping to shield them from life on the streets.

Since she began collaborating with Cob on Wood, she says, there is a place where she feels that they can safely and comfortably spend time with her. Her work here has also helped inspire her to pursue new opportunities.

“It has been a journey and it’s been hard,” she says. “But being a part of this and doing this work is getting me motivated.” She plans to launch a zine in the coming months, called From the Gutter, that she hopes will be a platform for unhoused people to share stories and tips.

“This is empowering us and making us feel good about ourselves again,” she says. “Helping us earn our living, and not have to beg for it, or steal it, or commit crimes.”

Mostly, though, like Dmitri Schusterman, she says it’s all about coming together.

“It is like a big family,” she says. “We have to make do with what we got. And if we have each other’s backs we can do that.”