How ‘Tangled Titles’ Affect Philadelphia

Editor’s note: This report was updated on Aug. 11, 2021, to correct the source information for Table 6.

Overview

Officials in Philadelphia and elsewhere have long grappled with the issue of “tangled titles” for homes—situations in which the deed to a property bears the name of someone other than the apparent owner. Tangled titles can have serious ramifications for residents and neighborhoods, sometimes causing people to lose their primary residence or be unable to manage its upkeep.

These title issues deprive individuals and families of the full benefit of owning a home. Without clear ownership, residents are unable to tap into the home’s value—in many cases, a family’s primary source of accumulated wealth. They can’t sell the property or take out a home equity loan. In most cases, they can’t get homeowner’s insurance or readily qualify for city programs aimed at helping low-income households. Yet at the same time, they’re still obligated to pay their real estate taxes, maintain their properties, and fulfill the other responsibilities of homeownership.

These barriers likewise affect a community’s stability, because homes with tangled titles are prone to falling into disrepair and even becoming abandoned, causing blight and displacement, and reducing the inventory of affordable housing.

Tangled titles—which are not unique to Philadelphia, and which are sometimes referred to elsewhere as “heirs’ property”—can come about in several ways. In the most common scenario, the owner of record dies and a relative inherits the property but fails to record a new deed. The existence of a will, although helpful in obtaining a title, is not enough in itself; a tangled title can still result unless the will goes through the legal process known as probate and a new deed is filed with the city records department.

The Pew Charitable Trusts set out to examine the problem of tangled titles and determine how prevalent it is in Philadelphia. Among the key findings:

- Philadelphia has at least 10,407 tangled titles, affecting 2% of the city’s 509,258 residential properties.1

- Although the median assessed value of these homes—$88,800—is lower than the citywide median of $134,300, the properties are still collectively worth over $1.1 billion, representing a significant amount of family wealth.

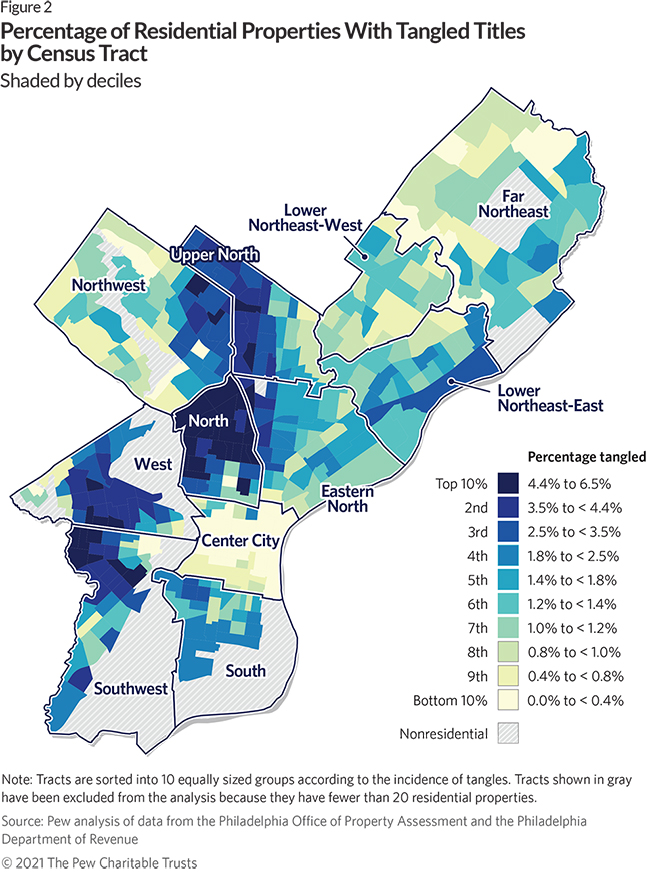

- The incidence of tangled titles is highest in parts of North, Upper North, West, and Southwest Philadelphia, areas that account for more than half of the city’s tangled titles but only about a third of all residential properties.

- Although no demographic data on affected households is available, the neighborhoods most affected tend to be those with relatively low housing values, low incomes, and high poverty rates.

- The populations of the hardest-hit areas are predominantly Black, while those least affected are majority White.

- Resolving a tangled title—which usually requires an attorney—can be time-consuming, tedious, and expensive. Without subsidized legal counsel, fee waivers, or other public assistance, the cost of remedying a tangled title can be significant: about $9,200 for a home valued at the median of $88,800.

Residents of a home with a tangled title may go for years without knowing they have a legal problem. They often learn of it when they encounter financial trouble and find themselves shut out of resources that could help them. As Philadelphia Commissioner of Records James Leonard put it: “The tangled title will sit there, and it never goes away. You will find out it’s a problem when you can least afford to do so.”2

Resolving the issue can be daunting, particularly for households with limited means, and there are different paths toward resolution depending on how the title came to be tangled.

The city has taken measures to help low-income households navigate the process of untangling a title—such as financing a Tangled Title Fund to help defray the costs—and is educating people about how to prevent tangles in the first place. But if the volume and impact of tangled titles are to be reduced in Philadelphia, vulnerable homeowners need to be aware of the problem, how they can avoid it, and how they can fix it.

Glossary

Below are key terms used throughout the report.

- Deed: A formal written document that transfers a title to a new owner and serves as proof of ownership. Although often used interchangeably with “title,” the term “deed” refers to a physical document.

- Heir: A person who, either through a will or through intestacy, has a legal claim to a deceased person’s property.

- Intestacy: State law governing distribution of the property of a person who dies without a will.

- Lien: A legal claim against a property that functions as collateral for debt.

- Personal representative: The modern label for the person responsible for settling an estate and carrying out the provisions of a will, if one exists. It encompasses the terms “executor”/“executrix,” formerly used when there was a will, and “administrator”/“administratrix,” which were used when there was not.

- Probate: The legal process of administering an estate after someone dies. Legally, the term “probate” applies only to estates that involve a will, and the term “estate administration” applies to those without one.

- Record owner: A person or other legal entity named on the deed recorded with the Department of Records.

- Title: The legal right to ownership of a property.

The extent of tangled titles in Philadelphia

The term “tangled title,” as used in Philadelphia, refers to a property for which ownership is unclear. The property can be subject to multiple overlapping legal claims, forming the metaphorical knot for which the predicament is named.

In many cases, the would-be owners do not realize that there is an issue.

“My mother passed away, and I had the house, but I never put the house in my name,” said Monique Spicer, 48, of North Philadelphia, a mother of four. “I was her only heir. I was thinking it automatically went to me.”3

To estimate the number of properties with tangled titles, Pew sought to establish how many residences’ titles are tangled because they are recorded in the names of people who have died. The researchers did this by submitting residential properties’ record owner names and addresses to a data service that checked them against a proprietary database built around the Social Security Administration’s Death Master File. The service identified individuals who had been dead for more than two years, long enough for their estates to have been handled in the normal course of probate.

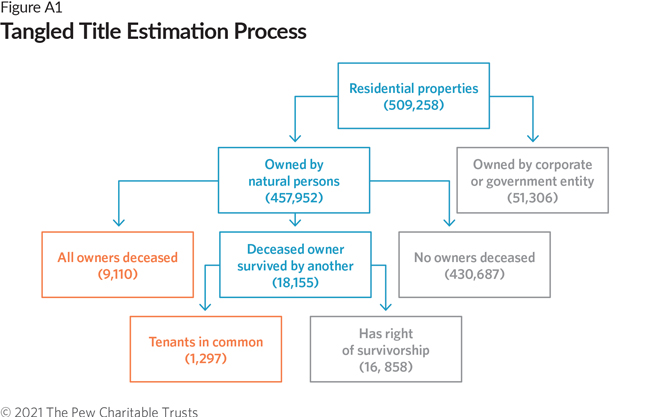

This process counted two types of tangled titles: properties for which a record owner’s death left no surviving record owners (9,110 properties) and those for which a record owner’s death left a surviving record owner to whom ownership would not automatically transfer (1,297 properties).

The estimate of 10,407 tangled titles in Philadelphia is undoubtedly an undercount, primarily because of two significant limitations in the method used to compile the figure.

First, the method identifies only tangled titles that result from a property owner’s death, which is by far the most common but not the only way for a title to become tangled. Second, in order to be flagged as deceased, an owner had to be listed in the death records with the same name and address that appeared on the deed. As a result, this process fails to include some owners who changed their names, held multiple properties, or moved to different addresses before their deaths.

In 2007, the legal services nonprofit Philadelphia VIP estimated that there were 14,001 tangled titles in the city.4 Pew’s analysis used a stricter definition of what constitutes a tangled title than did VIP, precluding direct comparison between the two estimates.

The appendix provides additional details on the methodology and a comparison between the current estimate and VIP’s 2007 estimate.

Characteristics of properties with tangled titles

The median assessed value of the tangled properties ($88,800) is lower than the citywide median of $134,300 not because of the tangled titles but because property values in the neighborhoods where the residences are located are lower than those in other areas of the city. In fact, the values of properties with tangled titles are only 1% lower, on average, than those of other properties on the same block.5

Tangled titles exist in every part of the city; the largest number are found in North, Upper North, Southwest, and West Philadelphia. (See Table 1.) Combined, these areas account for more than half of all tangled titles in Philadelphia, even though they contain only about a third of the city’s residential properties.

Table 1

Tangled Title Properties in Philadelphia by Census Public Use Microdata Areas

Largest numbers found in North, Upper North, Southwest, and West Philadelphia

| Census Public Use Microdata Area | Number of tangled title properties | Median assessed value of tangled properties | Aggregate assessed value of tangled properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| North |

1,716 |

$40,100 |

$84,682,000 |

| Upper North |

1,465 |

$107,100 |

$158,545,700 |

| Southwest |

1,427 |

$72,600 |

$118,947,100 |

| West |

1,249 |

$68,000 |

$100,416,100 |

| Eastern North |

1,078 |

$47,200 |

$78,789,700 |

| South |

900 |

$155,300 |

$145,437,300 |

| Northwest |

816 |

$122,050 |

$120,112,000 |

| Lower Northeast-East |

598 |

$114,000 |

$68,819,300 |

| Far Northeast |

554 |

$206,000 |

$114,884,500 |

| Lower Northeast-West |

376 |

$163,400 |

$61,076,200 |

| Center City |

228 |

$348,300 |

$93,881,800 |

| Philadelphia |

10,407 |

$88,800 |

$1,145,591,700 |

Note: Pew has slightly altered the names of some Public Use Microdata Areas to make them correspond more directly to the sections of the city they cover.

Source: Pew analysis of data from the Philadelphia Office of Property Assessment and the Philadelphia Department of Revenue

© 2021 The Pew Charitable Trusts

Across the city, 32% of tangled properties are delinquent in paying their real estate taxes, compared with 9% of residential properties citywide. About 39% of tax-delinquent tangled title homes are in payment agreements with the city, a rate of participation higher than the average of 34% among all delinquent residential properties.6

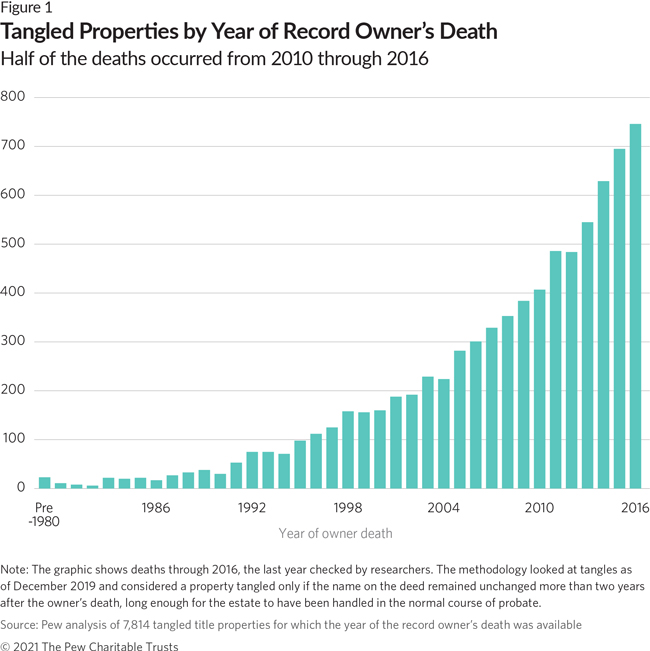

Half of the tangled titles in Philadelphia became tangled from 2010 through 2020; less than 20% date from the year 2000 or earlier. The fact that tangled titles tend to be connected to more recent deaths, as shown in Figure 1, suggests that the issues tend to get resolved over time—either through the remedies outlined in this report or by losing the house to sheriff’s sale or foreclosure.

Characteristics of neighborhoods by presence of tangled titles

As shown by census tract in Figure 2, properties with tangled titles represent a higher percentage of residential properties in some parts of Philadelphia than in others.

Table 2

Characteristics of Census Tracts by Presence of Tangled Titles

Tangles are more common in lower-income areas

| Tracts | Percentage tangled | Median house assessed value per square foot | Median household income | Poverty rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Top 10% |

4.4% to 6.5% |

$40 |

$28,636 |

34% |

|

2nd |

3.5% to < 4.4% |

$57 |

$30,426 |

32% |

|

3rd |

2.5% to < 3.5% |

$78 |

$33,533 |

31% |

|

4th |

1.8% to < 2.5% |

$103 |

$42,692 |

25% |

|

5th |

1.4% to < 1.8% |

$122 |

$46,907 |

23% |

|

6th |

1.2% to < 1.4% |

$118 |

$54,340 |

20% |

|

7th |

1.0% to < 1.2% |

$120 |

$44,233 |

24% |

|

8th |

0.8% to < 1.0% |

$132 |

$54,920 |

21% |

|

9th |

0.4% to < 0.8% |

$154 |

$66,676 |

17% |

|

Bottom 10% |

0.0% to < 0.4% |

$294 |

$75,098 |

17% |

|

Philadelphia |

0.0% to 6.5% |

$103 |

$45,927 |

24% |

Sources: Pew analysis of data from the Philadelphia Office of Property Assessment and the Philadelphia Department of Revenue; U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, five-year estimates, 2015-19

© 2021 The Pew Charitable Trusts

Although publicly available data does not include the characteristics of the households living in homes with tangled titles, the census tracts with higher percentages of tangled titles have lower household incomes and higher poverty rates than tracts with lower percentages of tangled titles. (See Table 2.) Among the other factors that help explain the prevalence of tangled titles in these areas are the inaccessibility of legal services and low property values, sometimes compounded by liens, that limit the financial benefit of clearing the title.

For the tracts in the group with the highest percentage of tangled titles, shown in dark blue in Figure 2, the median household income is $28,636, well below the citywide median of $45,927, and the poverty rate is 34%, 10 percentage points above the city’s overall rate of 24%. (See Table 2.) Residential properties in the most affected tracts are assessed at a median value of $40 per square foot.7 More than half of these tracts are in North Philadelphia.

For the group with the smallest percentage of tangled titles, shown in pale yellow in Figure 2, the median household income is relatively high, the poverty rate is relatively low, and home values are $294 per square foot. Nearly two-thirds of these tracts are in Center City.

There is also a clear correlation between the incidence of tangled titles in an area and residents’ race and ethnicity. The tracts with the highest rate of tangled titles are those in which Black residents constitute the largest percentage of the population. The inverse is true of the White and Asian American populations. Patterns are less clear-cut for Hispanics and other racial and ethnic groups. (See Table 3.)

Table 3

Race and Ethnicity in Census Tracts With Tangled Titles

Areas with higher percentages of tangles tend to have predominantly Black populations

| Tracts | Percentage tangled | Population | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Other/ two or more |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Top 10% |

4.4% to 6.5% |

129,084 |

5% |

87% |

4% |

2% |

3% |

|

2nd |

3.5% to < 4.4% |

162,464 |

4% |

84% |

9% |

1% |

2% |

|

3rd |

2.5% to < 3.5% |

148,701 |

9% |

73% |

13% |

3% |

2% |

|

4th |

1.8% to < 2.5% |

156,013 |

40% |

31% |

20% |

6% |

2% |

|

5th |

1.4% to < 1.8% |

163,153 |

41% |

30% |

21% |

6% |

2% |

|

6th |

1.2% to < 1.4% |

167,118 |

41% |

28% |

20% |

8% |

3% |

|

7th |

1.0% to < 1.2% |

178,225 |

44% |

27% |

16% |

10% |

3% |

|

8th |

0.8% to < 1.0% |

183,511 |

45% |

23% |

19% |

10% |

3% |

|

9th |

0.4% to < 0.8% |

162,943 |

52% |

21% |

13% |

11% |

4% |

|

Bottom 10% |

0.0% to < 0.4% |

114,009 |

62% |

13% |

7% |

14% |

3% |

|

Philadelphia |

0.0% to 6.5% |

1,579,075 |

34% |

41% |

15% |

7% |

3% |

Sources: Pew analysis of data from the Philadelphia Office of Property Assessment and the Philadelphia Department of Revenue; U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, five-year estimates, 2015-19

Note: The Philadelphia population total of 1,579,075 includes 13,854 people not included in the geographic breakdown because they live in census tracts with fewer than 20 residential properties—too few for the analysis shown here.

© 2021 The Pew Charitable Trusts

Low levels of estate planning among Black households likely contribute to the racial patterns shown in Table 3. Nationally, among people over age 50, only 20% of Black residents have valid wills, compared with 63% of White residents.8 And 49% of Black households in Philadelphia own their homes, the highest rate of Black homeownership among the 50 largest cities in the country.9

How a title gets tangled

A title can get tangled in one of five ways:

The necessary steps are not taken after the owner of record dies. This is by far the most common scenario by which ownership becomes tangled.10 When a record owner dies, the deed at the Department of Records continues to bear the name of the deceased unless the heirs take action.11 Establishing who has the right to the title is determined through a process called probate, which is guided either by a will declaring the deceased’s intentions or, in the absence of a will, by state inheritance laws. Depending on the circumstances, probate can be costly and potentially complicated—especially when no will exists—which is why some people, especially those with low incomes, don’t engage in the process. Costs include a probate fee, a deed recording fee, and inheritance taxes, with an attorney needed in most cases. And decisions must be made when a family is grieving and perhaps overwhelmed by all that must be done when a loved one dies. But until probate is completed and a new deed is recorded, the title remains tangled.12

A rent-to-own agreement goes wrong. The title to a property can become tangled through a failed rent-to-own agreement, a method of home purchase sometimes used by people who are unable to secure a mortgage.13 The buyer agrees to make installment payments over a period of time while living in and caring for the house. The seller agrees to transfer the title to the buyer when the payments are completed. Entering the agreement gives the buyer a legal claim to the property, although the seller remains the record owner for the duration. If the seller fails to transfer a clean title to the buyer after the agreed-upon payments are made, the title becomes tangled.14

The owner abandons the property. Sometimes, a landlord stops collecting rent or attending to a property, leaving the tenant to continue living in the home undisturbed, effectively assuming the role of property owner. If this condition persists for more than 10 years without challenge or permission from the record owner, the long-term occupant can make a claim to ownership under Pennsylvania law. This is known as “adverse possession.”15

The transaction is not properly recorded. A tangle also can result from a deed transfer not being properly documented with the Department of Records. In some cases, the seller, after having taken responsibility for recording the deed transfer, fails to do so. By the time the buyer realizes what has happened, the seller could be unreachable or uncooperative—resulting in a tangled title.16

The deed is stolen. Titles can become tangled through deed theft—also known as fraudulent conveyance—when a property is unlawfully transferred to a new owner. The perpetrator of the fraud either forges the record owner’s signature or coerces or deceives the owner into signing it away. This type of fraud often occurs when a property has been left vacant. By the time the rightful owner realizes that the property has been stolen, there could be new occupants who believe that they rightfully purchased the home, adding an additional layer of complication.17

How tangled titles put owners and the community at risk

Somebody living in a home with a tangled title still has all the obligations of homeownership—such as paying real estate taxes and maintaining the property—but few of the resources and protections enjoyed by deed holders. This ambiguity undercuts individual and family wealth, the preservation of affordable housing, and, ultimately, neighborhoods’ stability.

With a tangled title, in most cases, one can’t sell the home, take out a home equity loan, obtain homeowner’s insurance, or participate in city home repair programs—and most people face obstacles in participating in city relief programs for homeowners struggling with real estate taxes or water department charges.18 These limitations can put a home at greater risk of deterioration, foreclosure, and, in some cases, theft.

Michael Schwartz, who lived for eight years in his family’s longtime Northeast Philadelphia home before getting the title untangled, talked about the difference that obtaining a title has made. “I went to a lot of places, and they told me, ‘You don’t own the house and you can’t get the help,’” said Schwartz, 60. “And now I do, and now I can. I can now say, ‘Here’s the deed, what can we do?’”19

Risk to wealth building

Homeownership is an important tool for building wealth, particularly across generations. In areas with rising property values, like many sections of Philadelphia, the house captures years of value appreciation. A property with a tangled title is effectively “dead capital”; the owners cannot access the home’s equity as collateral to obtain a bank loan to improve the property or invest in a business.20 Furthermore, without a deed, they can’t sell the property or establish an estate plan to legally pass it on to prospective heirs.

Risk of deterioration

Maintenance can be a significant household expense—particularly for older homes, which are prevalent in Philadelphia. (More than half of the city’s housing was built before 1949.21) Older people may have additional maintenance costs stemming from accessibility accommodations needed to allow them to safely age in place.

Philadelphia has several programs, both grants and loans, to help low-income homeowners make home improvements. But the application for assistance will be denied if the title is tangled.22

For low-income households with tangled titles, damage from a storm, a leaky pipe, or a kitchen fire can be devastating. A homeowner’s insurance policy would cover the costs, but tangled properties are generally not eligible for coverage. Even if the residents had kept paying premiums on a policy that the record owner opened before he or she died, the insurance company may not be obligated to honor that policy.23 And federal disaster relief for a damaged property can be denied if the applicant is unable to demonstrate ownership.24

Gina Miller, a 60-year-old West Philadelphia resident, has lived in her home since 1979. “Just recently, the main sewer line broke, and I thought I was going to have to pay over $2,500 to fix it, which I can’t afford because I live off Social Security,” she said. “I didn’t qualify for repair programs, since I’m not on the deed of the property.” A volunteer attorney helped Miller secure financing for the sewer repair and is working with her to untangle the title.25

Risk to neighborhood quality and stability

Over time, tangled ownership can lead to deterioration of the property through lack of upkeep, potentially becoming a danger to its inhabitants and a blight to the surrounding area. The occupant’s inability to get loans or assistance increases the chances that he or she will be unable to maintain it, perhaps leading to abandonment. Losing these lower-priced properties to maintenance issues reduces the supply of affordable housing.

And blighted or boarded-up buildings can have significant consequences for the community: Neglected properties can bring down neighboring homes’ values, increase crime rates and cleanup costs for the city, and pose fire hazards.26 Over the past several years, according to David Perri, former commissioner of the Department of Licenses and Inspections, almost all building collapses in the city not involving construction activity were caused by a lack of maintenance. Many of those buildings had tangled titles.27

Perri recalled a rash of building collapses around the time he became commissioner in 2016. In one example from North Philadelphia, years of water infiltration from a failing roof brought down a tangled title home while its inhabitants—who only narrowly escaped—were still inside. The home had been owned by an aunt who died, and the residents couldn’t afford to maintain it. With a new roof, which city repair programs might have been able to help with if not for the tangled title, the house might have been saved.

Risk of foreclosure

Nonpayment of property tax bills or water/sewage charges can result in foreclosure. Philadelphia’s revenue and water departments both offer payment plans for low-income payers who struggle with their bills, helping them avoid those situations. But taking advantage of these programs can be challenging with a tangled title.

The revenue department allows owners with a tangled title to enter into property tax payment agreements if they can demonstrate what the city deems to be sufficient proof of ownership, such as the record owner’s death certificate and the applicant’s birth certificate listing the record owner as parent. Homeowners then have three years to resolve the tangled title.28

Owners without a deed can enter into an agreement with the water department if the bill is in their names. But getting on the bill requires evidence of the record owner’s permission to live at the property. An owner with a tangled title may need a written statement from an attorney.29

Risk of deed theft

Properties with tangled titles, particularly those where the record owner has died and the home has no regular occupants, are vulnerable to property theft through forged signatures. The perpetrator sells the house to an unwitting buyer and takes the profits, thereby stripping the rightful heirs of their family’s property and accumulated wealth.30

How to remedy a tangled title

A tangled title occurs when the apparent owner has a legal claim to a property that is not reflected in official records. Depending on the circumstances, people can explore three possible avenues to try to clear a tangle: Go through the probate process with the Register of Wills, file a petition in Orphans’ Court, or file a “quiet title action” lawsuit in Common Pleas Court. In almost all circumstances, an attorney is required.

Table 4 summarizes the options, which are explained in greater detail below.

Table 4

Options for Remedying a Tangled Title

| Circumstance | Remedy |

|---|---|

|

Probate |

|

Court |

|

File quiet title action |

Probate

Probate is the legal procedure for dealing with a person’s debts and assets—collectively referred to as an estate— after he or she dies, ensuring that anyone with an interest has an opportunity to make a claim. If the estate’s assets include a piece of real property, and probate is not initiated, a tangled title is the inevitable result. Just as a tangled title persists until someone clears it up, access to probate is available until the deceased’s affairs are settled—whether the death occurred three days ago or three decades ago.

The word “probate” is derived from the Latin word for “prove.”To probate an estate is to prove that the actions taken by the living are in accordance with the wishes of the deceased. In the case of real property, probate asks: “To whom should ownership of this property pass?”

If the deceased person left a will and his or her heirs know where to find it, that question can be easy to answer.

If there is no will, or if the will does not answer the question, then, in the words of Philadelphia Register of Wills Tracey Gordon, “The state of Pennsylvania has [an answer] for you: It’s called intestacy.”31 Under intestacy, ownership is divided among the closest living relatives, following a sequence of priority that starts with a spouse and ends with the children of first cousins, with multiple possible permutations in between. In the absence of any heirs, ownership passes to the state.32

In Philadelphia, the Register of Wills’ office oversees probate. The process can take a year or more, with notification requirements taking up most of that time and several fees to be paid at various stages, which can make the process cost-prohibitive for people with low incomes. Approximately 3,000 properties per year are transferred in Philadelphia as a result of the probate process.33

Passing the title to a new owner via probate can be relatively straightforward if the will is clear. And things can go just as smoothly without a will, if the individual taking the title has the support of all other heirs.

Dealing With Shared Ownership

If the deceased person was not the property’s sole owner, whether probate is necessary to prevent a tangled title depends on the form of shared ownership: that is, whether it is joint tenancy or tenancy by the entirety—both of which include the right of survivorship—or tenancy in common, which does not.34 The form of ownership should be specified on any deed that bears the names of more than one owner. (See Table 5.)

With joint tenancy, the entire property is owned equally by each person on the deed. If one of them dies, the deceased person’s ownership share automatically goes to the surviving owner or owners, and probate is not necessary. Tenancy by the entirety, which applies only to married couples, functions the same way. With tenancy in common, each person owns a specific but not necessarily equal share. When one owner dies, the deceased person’s share passes to his or her estate rather than to the surviving owners, and probate is necessary.

If a deed with multiple owners does not specify the form of shared ownership, the default form is tenancy in common unless the grantees are a married couple, in which case it’s tenancy by the entirety. If the couple has divorced, probate is necessary when either person dies.An unmarried couple who buy a house as tenants in common and later marry will need a new deed to change the form of ownership.35

For properties owned by tenants in common, the death of one owner results in a tangled title unless the deceased’s estate goes through probate and a new deed is recorded. Until that happens, the surviving owner or owners cannot take any action that requires the consent of all record owners—such as selling the home, taking out a home equity loan, or getting home repair assistance from the city.

Table 5

Forms of Shared Ownership

| Ownership | Available to | How it works | Right of survivorship |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Joint tenancy |

Two or more owners |

Each has equal claim to ownership |

Yes, claim passes to surviving owners |

|

Tenancy by the entirety |

Married couples |

Married couple as a unit has full ownership |

Yes, ownership passes to surviving spouse |

|

Tenancy in common |

Two or more owners |

Each has a specific fractional share of ownership |

No, fractional claim passes to estate |

© 2021 The Pew Charitable Trusts

The key aspects of clearing a tangled title via probate are as follows:

Initiate probate. Probate begins with a petition to appoint the petitioner as the personal representative of the estate, making him or her officially responsible for the process. The petition form—which includes information about the deceased, surviving heirs, and the estate—must be accompanied by the death certificate and a will, if one exists; the will often designates the personal representative. In the absence of a will, the filing will need the support of all intestate heirs. If the heirs cannot agree, the Register of Wills makes the determination.36

The probate fee, which is based on the value of the estate, is due along with the petition. The Register of Wills’ base fees are set by state law.37 For an estate whose only asset is a house with the median value of tangled title properties in this analysis ($88,800), the probate fee would be $475.38

Recognizing that the fee can deter lower-income households from initiating the process—a root cause of tangled titles—the Register of Wills has launched a pilot program, the Probate Deferment Initiative, for low-income applicants working with an attorney. For those in the program, the fee is not collected with the application but instead is recorded as a lien against the property, effectively deferring payment until the property is sold.39

Notify interested parties. The personal representative bears responsibility for notifying all parties who may have a claim to the deceased person’s assets. Anyone who would be an heir under intestate, regardless of whether a will exists, and any known creditors should be notified by mail or in person.40 To alert any potentially unknown creditors, the estate should be advertised once a week for three weeks in both a general circulation newspaper and a publication that serves the legal community, which in Philadelphia costs $518.41 Heirs and creditors have one year from notification to come forward. The personal representative is forever financially liable for the claims of any party who was not properly notified.42

Settle debts. The personal representative is responsible for paying the deceased person’s creditors, and the estate’s assets can be used to settle debts. If the house is the only asset, the personal representative must find another way to pay the debts to avoid selling it.43 Federal law treats a mortgage differently from other debts, requiring creditors to allow a relative inheriting the property to assume mortgage payments instead of paying off the balance outright, as is typically required when a property changes hands.44

Distribute assets and pay taxes. Assets distributed to heirs are subject to state inheritance tax. The tax is due upon the decedent’s death, discounted by 5% for three months from that date, and then becomes delinquent after nine months.45 The taxable value of distributed assets may be reduced by deducting the debts of the deceased, funeral expenses, estate administrative costs, and, in some cases, a small family exemption.46 The tax rate is 4.5% for children, parents, and grandparents; 12% for siblings; and 15% for anyone else. The spouse of the deceased and children age 21 or younger are exempt, as are the parents if the deceased was 21 or younger.47 The average tangled title property in Pew’s analysis was valued at $88,800, which, without any deductions, would trigger approximately $4,000 in taxes if it were distributed to a child, parent, or grandparent of the deceased; $10,700 in taxes for a sibling; and $13,300 in taxes for any other heir.

Draft and record a new deed. To make the heir taking the title the owner of record, a new deed must be drafted and recorded with the Department of Records. Upon recording, the heir becomes the record owner. The fee is $256.75, which can be waived in tangled title cases brought by attorneys working with legal aid organizations.48 Paperwork for the real estate transfer tax, which is 4.278% of the property’s value, must also be filed at this time, even though most heirs taking titles via probate are exempt from paying it.49

The Cost of Probate

How much does it cost to resolve a tangled title via probate, assuming no subsidized legal assistance, fee waivers, or assistance from the city’s Tangled Title Fund? The answer varies based on several factors, including the home’s value.

Consider a simple case: A person wants to obtain the title for the home of his or her deceased parents, both of whom died without a will several years ago. He or she is the only heir to the property, and the deceased person left no other debts or assets. The property was assessed at $88,800 at the time of death. The individual hires an attorney to handle everything.

As shown in Table 6, the total cost in this case would be $9,198. This suggests that remedying 10,407 tangled titles is roughly a $96 million problem—a significant amount but less than a tenth of the value of real estate at risk.

Table 6

Total Cost of Probate in a Simple Case

Biggest items are inheritance tax and attorneys fees

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

|

Attorneys fees* |

$4,440 |

|

Inheritance tax† |

$3,508 |

|

Advertising cost |

$518 |

|

Probate fee |

$475 |

|

Recording fee |

$257 |

|

Total |

$9,198 |

Source: Pew calculations based on fee schedules, tax rates, and other cost estimates

Note: Calculation for an estate with no debts and a home valued at $88,800 as the only asset.

* Five percent of the estate’s gross value, based on the generally accepted industry standard.

† The inheritance tax is 4.5% (the inheritance tax rate for a child of the deceased) multiplied by the estate’s adjusted value, $77,960—the value of the house ($88,800) minus the fees and costs listed above (excluding the inheritance tax), as well as $5,150 in funeral expenses (the median cost of a funeral with cremation, according to the National Funeral Directors Association).

© 2021 The Pew Charitable Trusts

Orphans’ Court petition

In certain circumstances in which a tangled title stems from a record owner’s death, someone looking to obtain a property’s title can avoid probate by directly petitioning the Orphans’ Court.50 Filing fees for most petitions are $90.25, which the court can waive for low-income petitioners.51

The legal action, “petition for determination of title to decedent’s interest in real estate,” can be filed under two sets of circumstances:

- If a year has passed since the death and no estate has been opened.

- If six years have passed since the death and an estate was opened but the process was not completed.52

In this process, the notification, debt, and tax obligations are similar to those of probate. The key difference is that the petition does not require active participation of all other heirs, but the petitioner must demonstrate an exhaustive effort to locate and contact as many as possible. The effort typically involves discussing each person’s whereabouts with other relatives, sending a Freedom of Information request to the U.S. Postal Service for lastknown address, speaking with the last-known employer, and searching the internet, among other things. Twenty-five or fewer such petitions are filed each year.53

Quiet title action

“Quiet title” is the blanket term for lawsuits over claims to property. Whereas probate and Orphans’ Court petitions deal with tangled titles connected with a death, quiet title actions are filed in Common Pleas Court to settle disputes among the living in several specific situations:

- A failed rent-to-own agreement, in which the seller refuses to transfer the title or the buyer is in default.

- Fraudulent conveyance, in which the property was stolen by a forged signature, deceit, or coercion.

- A transaction that was never properly recorded.

- Adverse possession.54

The filing fee for a quiet title action is $333.23, which the courts can waive for low-income people.55

Choosing not to remedy a tangled title

In some cases—for instance, when there’s a heightened risk of losing the home—opting not to resolve a tangled title might be preferable. Two potential sets of concerns:

Financial considerations

When an estate has significant debts, an heir may decide it is not financially prudent to pursue a title because the debts come with the house. As personal representative of the estate or as a petitioner in Orphans’ Court, the heir seeking the title is responsible for settling the deceased’s debts, which may require selling the house. Furthermore, if there is a lien on the home, the person looking to take the title may not be comfortable assuming the risk of foreclosure that comes along with it.

For example, if the deceased record owner received Medical Assistance for long-term care at age 55 or older, federal law requires the state to recover the cost of care from any assets left behind, including a house.56 These costs can amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars.57 The Pennsylvania Department of Human Services can waive recovery if the heir taking title provided care to the deceased for at least two years and has no other address or can otherwise demonstrate hardship. Recovery may also be postponed in some circumstances.

Otherwise, the state can seize the home.58

Other heirs

Untangling a title requires notification of other heirs, alerting them to ownership claims of which they may not be aware. Satisfying their claims may require selling the property and dividing the proceeds—which the home’s current occupant might not want to do.

Legal and financial assistance

The tangled title remedies described in this report can be difficult, if not impossible, for a homeowner to navigate without legal assistance. Hiring an attorney can be prohibitively expensive for some. Low-income individuals who have tangled titles and intend to live in the homes may be able to get free legal help from organizations such as Community Legal Services (CLS), SeniorLAW Center, and Philadelphia Legal Assistance (PLA), or be connected to attorneys working pro bono through Philadelphia VIP.

For expenses that cannot be waived for low-income applicants—such as the real estate transfer tax or the cost of newspaper advertising—attorneys working with CLS, SeniorLAW, PLA, and VIP can apply for grants from the city’s Tangled Title Fund (TTF), administered by VIP. Each year, TTF provides 50 to 100 grants of $1,700 on average, up to $4,000.59

How individuals and families can prevent tangled titles

Make a will

By making the deceased person’s wishes explicit, a will reduces the amount of uncertainty and complication that heirs encounter during probate. Gordon, the register of wills, said that Philadelphians “need a will when they get assets—not when they get old,” likening a will to insurance that helps preserve accumulated wealth across generations.60 It’s important that heirs—especially the person named as personal representative—know where to find the will. A will signed by the person making it and two witnesses in the presence of a notary public will be accepted in the probate process.61

Probate estate after property owner’s death

The record owner’s death will inevitably lead to a tangled title if the deed is not transferred to a new owner via probate. Although it may not be top of mind for grieving loved ones, the probate process should be initiated as soon as possible. Simple estates that are dealt with promptly can be handled largely without an attorney.

Sign up for Fraud Guard

Philadelphia’s Department of Records offers a notification service called Fraud Guard to alert homeowners of possible deed theft. Homeowners who opt into the service receive an email alert anytime their name appears in a recorded transaction. The alerted homeowner can then view the transaction details online to determine their legitimacy. Fraud Guard cannot prevent the theft, but it does allow defrauded homeowners to recognize and report the crime before further damage is done.62

Conclusion

It’s easy for a property’s title to become tangled, especially after a record owner dies. Do nothing, and a tangled title is inevitable. Preventing or clearing a tangled title, on the other hand, is not so easy, even in the simplest of cases. Heirs must actively engage in the probate process and marshal the resources to go through it.

The city of Philadelphia and other organizations are taking steps to help low-income households prevent and resolve tangled titles. They include:

- Educational programs—such as the Register of Wills’ “Plan, Prepare, Protect” tour of civic group meetings— to ensure that homeowners know what a tangled title is, how probate works, and why a will is important.

- Resources for applicants turned away from city support programs for lack of a deed demonstrating ownership, and, where possible, allowing provisional participation in these programs while the tangled title is being remedied.

- Fee deferrals and waivers to make clearing a tangle less costly, such as those offered to low-income individuals by the Register of Wills for probate fees, by the Department of Records for recording fees, and by the courts for filing fees.

- Free legal assistance for those without the means to pay, such as that provided by CLS and others or arranged by VIP.

- Public funding to cover costs that cannot be waived or deferred, such as inheritance and transfer taxes, which the city-funded Tangled Title Fund is able to cover for some residents.

Even with such efforts, Philadelphia has over 10,000 tangled titles affecting real estate worth more than $1.1 billion. Resolving those tangles—and preventing more from occurring—will help preserve family wealth, the city’s housing stock, and neighborhood quality.

Appendix A

Estimating tangled titles

To arrive at the estimate of 10,407 tangled titles, Pew reviewed property ownership data for 509,258 residential properties and submitted record owners’ names and addresses to a service that checked them against a proprietary database built around the Social Security Administration’s Death Master File. Pew’s estimate of tangled titles has two components: (1) properties for which all of the record owners are deceased, and (2) properties for which at least one but not all owners are deceased and that appear to be owned by tenants in common.

Data sources

The estimation process relied on four data sources:

- Office of Property Assessment (OPA) records. A complete dataset of the location, characteristics, ownership, and assessed market value of land and improvements for all real estate in Philadelphia. Ownership data, which is based on the most recent deed transaction, is updated on a roughly three-month lag from time of sale. The file was downloaded in December 2019.

- Real estate transfers (RTT). A dataset of all real estate transfers that the Department of Records recorded beginning in December 1999. The dataset is based on the Department of Records’ legal administrative records and enhanced to include the corresponding OPA record number. The file was downloaded in December 2019.

- Digitized recorded deeds (PhilaDox). An online repository of scanned and indexed documents recorded by the Philadelphia Department of Records from 1974 to the present.

- Deceased suppression service. Using a proprietary database of death records from the Social Security Administration’s Death Master File paired with addresses, the service flags deceased individuals. Death records are on a lag of approximately three years; this analysis includes deaths that occurred through 2016. Pew used the service in May and August 2020.

Compiling residential ownership file

Residential property addresses and assessed values were drawn from OPA. The definition of “residential” for this analysis includes single-family homes, condominium units, multifamily properties with four or fewer units, and neighborhood-scale mixed-use properties (e.g., a street-level storefront with a residence on the upper floors). Apartment buildings with five or more units, dormitories, boarding houses, prisons, and nursing homes were excluded, as they are generally not owned by individuals living at the property. A total of 509,258 residential properties were included. American Community Survey data shows that approximately 85% of Philadelphia’s population lives in the type of housing included in this study.63

Owner names were drawn from the RTT for 89% of properties that had a relevant transaction in the data. Names were sourced from the most recent deed, or, if there was no deed, the most recent mortgage-related document. For the other 11% of properties, owner names were taken directly from the OPA data. Ownership information should be the same in both datasets; however, the RTT was preferred because names are formatted consistently and because there is no cap on the number of owners recorded, whereas the OPA data is limited to two owners.

Estimating tangled titles

Pew’s tangled title estimate is the result of the multistep process described below and in Figure A1. The estimated number of tangled titles, 10,407, is the sum of the two orange boxes.

The process began by excluding approximately 10% of properties (51,306) because they were owned by corporate or government entities. Record owner name-address pairs for the remaining 457,952 properties owned by individuals were then sent to the deceased suppression service to check against its proprietary database of death records.

The analysis looked only for record owners who had been dead for more than two years. The idea was to avoid picking up properties that might still be in probate—a process that need not be initiated immediately after a death and which can routinely take a year or more.

The results of the death records check showed that 9,110 properties had no surviving owners, and Pew classified them as tangled titles. The records check also found 18,155 properties for which there were multiple owners, at least one of whom was deceased. Whether any of those properties had tangled titles depended on whether the owners had been tenants in common. If so, the deceased’s share of the property would pass to his or her heirs, and that would need to be recorded on a new deed. Without a new deed, the title would be tangled.

Pew decided not to undertake the time-consuming task of examining all 18,155 properties individually to determine the form of shared ownership in each case. Instead, the researchers examined a random 1% sample of the deeds, accessed via the Department of Records’ PhilaDox website. Of the 182 deeds sampled, 7.1% were owned by tenants in common and therefore likely to be tangled. If that percentage held true for all 18,155 properties, the additional number of tangled titles would be 1,297.

The two forms of tangled titles combined produce the citywide estimate of 10,407.

Those 1,297 additional tangled titles were allocated to the various Census Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMAs) based on both the number of properties in each PUMA with one but not all owners deceased and the rate of other tangled titles in each PUMA. A second round of disaggregation apportioned the PUMA-level estimates to the component tracts in the same manner. Properties were assigned the median value of tangled title homes in that PUMA.

Limitations

The approach almost certainly produced an undercount of tangled titles because of limitations in the data. First, the tangles identified are only those that result from a legal owner’s death; as discussed in this report, a tangle can occur in other ways as well. Second, to be flagged as deceased, an owner would have to appear in the death records with the same name and address as in the property record. That requirement likely overlooked owners who changed names, held multiple properties, or moved to different addresses before their death.

Comparison with 2007 Philadelphia VIP estimate

In 2007, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s Cartographic Modeling Lab estimated the number of tangled titles in the city for Philadelphia VIP.64 That analysis produced an estimate of 14,001 properties. Due to financial constraints, the researchers working for VIP made several assumptions to limit the number of record owners’ names that needed to be checked to see if they had died. Pew made no such assumptions and checked all names for all years, producing a result that the researchers consider to be more accurate than the 2007 figure. Table A1 outlines the key differences between these estimates.

Table A1

Comparison of Methodology VIP 2007 and Pew 2021

| Ownership established through |

OPA |

OPA and RTT |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership established through |

OPA |

OPA and RTT |

| Number of owners’ names checked* |

One |

Multiple (all)* |

| Transaction years checked against death data |

1941-77 |

All years |

| Assumptions pertaining to most recent year of sale† |

14,001 |

None (all years checked) |

| Estimated number of properties with tangled titles |

Before 1941, tangled; after 1977, not tangled † |

10,407 |

* For properties with more than one owner (36% of properties in Pew’s 2021 analysis), VIP’s 2007 analysis checked only the name of the owner listed first.

† VIP’s 2007 analysis assumed that the owner of any property last sold in 1941 or earlier was likely deceased and that, therefore, the property had a tangled title. For all properties last sold after 1977, the analysis assumed that the owner was likely alive and that the title was not tangled.

© 2021 The Pew Charitable Trusts

In the researchers’ view, the differences in methodology mean that Pew’s findings are based on a more thorough vetting of the data and, ultimately, a stricter standard of what constitutes a tangled title than the 2007 estimate. If the 2007 VIP criteria were applied to Pew’s more recent data, the resulting estimate would be 12,497 tangled title properties.

Endnotes

- For this analysis, the definition of “residential” is restricted to places where the occupant may reasonably be expected to be the owner— including single-family homes, condominium units, small apartment buildings of two to four units, and neighborhood-scale mixed-use buildings such as corner stores with residences above. Large apartment buildings, dormitories, nursing homes, boarding houses, and prisons are excluded.

- J. Leonard (commissioner of records, Philadelphia Department of Records), interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, Dec. 7, 2020.

- M. Spicer, interview with Philadelphia VIP, March 2021.

- Philadelphia VIP, “Tangled Titles: An Obstacle to Stability for Low-Income Philadelphians” (2007).

- Pew calculation from Office of Property Assessment data.

- Pew calculation from Philadelphia Department of Revenue Property Tax Delinquencies dataset.

- Inclusive of land value.

- S.L. Choi et al., “Estate Planning Among Older Americans: The Moderating Role of Race and Ethnicity,” Financial Planning Review 2, no. 3-4 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1002/cfp2.1058.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Table B25003b-Tenure (Black or African American Alone Householder), 2019 one-year estimates, http://data.census.gov/

- Pew’s review of summaries of tangled title cases that Philadelphia VIP referred to pro bono attorneys between 2013 and 2020 found that approximately 75% were attributable to the record owner’s death.

- If no heir comes forward, a creditor of the deceased may also initiate the probate process.

- Philadelphia VIP, “Probate Training: Resolving Issues to Keep Clients in Their Homes” (2020), 16, https://www.phillyvip.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Training_Guide_Probate.pdf.

- Also known as a lease-purchase agreement or installment land contract.

- Philadelphia VIP, “Quiet Title Training Guide: Handling Cases Involving Problems With Title to Real Estate” (2019), 71, https://www.phillyvip.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Quiet-Title-Training-Manual.pdf.

- The 10-year standard applies to single-family homes on lots under one acre—a classification that includes 85% of properties in this analysis (Pew calculation). For other property types, the condition must persist for 21 years before an adverse possession claim can be made. R.E. Hamilton, E.R. Rollins, and A. Loza, “Adverse Possession in Pennsylvania” (WeConservePA, 2020), https://conservationtools.org/library_items/2137/files/2470.

- Philadelphia VIP, “Quiet Title Training Guide.”

- L. Benshoff, “Philadelphia Man Charged With Stealing 14 Homes Through Deed Theft,” WHYY.org, May 3, 2021, https://whyy.org/articles/philadelphia-man-charged-with-stealing-14-homes-through-deed-theft/.

- Tangled title properties for which a deceased record owner is survived by another record owner are still eligible to enter into payment agreements for property taxes and water department charges.

- D. Schwartz, interview with Philadelphia VIP, March 2021.

- C.J. Gaither and S.J. Zarnoch, “Unearthing ‘Dead Capital’: Heirs’ Property Prediction in Two U.S. Southern Counties,” Land Use Policy 67 (2017): 367-77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.05.009.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Table B25035-Median Year Structure Built, 2019 one-year estimates, http://data.census.gov/.

- J. Davis, public information officer, Philadelphia Housing Development Corp., multiple emails to The Pew Charitable Trusts, December 2020 to April 2021.

- HomeGo, “Guide to Homeowners Insurance on Inherited Property,” Oct. 9, 2019, https://www.homego.com/blog/homeowners-insurance-inherited-property/.

- C. Kane, S. Beaugh, and G. Sias, “Addressing Heirs’ Property in Louisiana: Lessons Learned, Post-Disaster,” in Heirs’ Property and Land Fractionation: Fostering Stable Ownership to Prevent Land Loss and Abandonment, eds. C.J. Gaither et al. (Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019), https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr_srs244.pdf.

- G. Miller, interview with Philadelphia VIP, March 2021.

- J. Schilling and J. Pinzón, “The Basics of Blight: Recent Research on Its Drivers, Impacts, and Interventions” (2016), http://vacantpropertyresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/20160126_Blight_FINAL.pdf.

- D. Perri (former commissioner, Philadelphia Department of Licenses and Inspections), interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, July 2019.

- Philadelphia Department of Revenue, “Owner Occupied Payment Agreement Application, Tangled Title Supplement” (2021), https://www.phila.gov/media/20210224083842/Application-Owner-Occupied-Payment-Agreement-OOPA-supplements-fillable-0221.pdf.

- R. Ballenger, senior supervising attorney, energy unit co-director, Community Legal Services, email to The Pew Charitable Trusts, January 2021.

- C.R. McCoy, “Stealing From the Dead,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 23, 2019, https://www.inquirer.com/news/a/house-sales-fraud-theft-philadelphia-real-estate-dead-owners-william-johnson-20190124.html.

- T. Gordon, Philadelphia register of wills, “Plan. Prepare. Protect. Virtual Tour” (presentation, Urban League of Philadelphia, Nov. 17, 2020).

- Pennsylvania 20 Pa. C.S.A. § 2103, https://codes.findlaw.com/pa/title-20-pacsa-decedents-estates-and-fiduciaries/pa-csa-sect-20-2103.html.

- Pew calculation from Real Estate Transfer Tax data.

- Social Security Administration, “Programs Operations Manual Systems, Sole vs. Shared Ownership,” last modified April 18, 2016, http://policy.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0501110510.

- M. Jones, homeownership staff attorney, Philadelphia VIP, email to The Pew Charitable Trusts, January 2021.

- Philadelphia Bar Association, “Philadelphia Estate Practioner Handbook—Register of Wills of Philadelphia County Manual (‘the Blue Book’)” (2002), 21-23, https://www.philadelphiabar.org/WebObjects/PBA.woa/Contents/WebServerResources/CMSResources/PEPH_blue.pdf.

- Pennsylvania 42 P.S. § 21017, https://codes.findlaw.com/pa/title-42-ps-judiciary-and-judicial-procedure/pa-st-sect-42-21017.html.

- Philadelphia Register of Wills, “Fee Schedule,” last modified Aug. 1, 2016, https://secureprod.phila.gov/row/fees.aspx. The fee for estates with assets valued between $50,000 and $200,000—a range that captures roughly two-thirds of the tangled title properties identified— is $475.25, according to Pew calculations.

- M. Bond, “Unclear Ownership Impedes Upkeep and Sale of Houses in Philly. The City Is Working on a Solution,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 4, 2021, https://www.inquirer.com/real-estate/housing/property-will-help-philadelphia-tangled-title-register-20210403.html.

- Philadelphia Bar Association, “Philadelphia Estate Practioner Handbook (‘the Blue Book’),” 33-34.

- As of May 2021, the Philadelphia Daily News charges $313.76 for an estate notice, and The Legal Intelligencer charges $204.

- Philadelphia VIP, “Probate Training,” 42-43.

- M. Randolph, “Paying Off Debts of the Estate,” Nolo, accessed May 11, 2021, https://www.alllaw.com/articles/nolo/wills-trusts/executors-paying-off-debts-estate.html.

- A. Loftsgordon, “Taking Over the Mortgage When Your Loved One Dies,” Nolo, accessed May 11, 2021, https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/taking-over-the-mortgage-when-your-loved-one-dies.html.

- Pennsylvania Department of Revenue, “Inheritance Tax,” accessed May 11, 2021, https://www.revenue.pa.gov/TaxTypes/InheritanceTax/Pages/default.aspx.

- The family exemption reduces the estate’s taxable value by $3,500 and may be claimed only by a spouse, a child living with the record owner at the time of death, or a parent living with the record owner at the time of death. Philadelphia VIP, “Pennsylvania Inheritance Tax Guide” (2020), 9, https://www.phillyvip.org/inheritance-tax-guide.

- Pennsylvania 72 P.S. § 9116, https://codes.findlaw.com/pa/title-72-ps-taxation-and-fiscal-affairs/pa-st-sect-72-9116.html.

- Leonard, interview.

- Spouses, siblings and their spouses, and direct descendants and their spouses are exempt, as are any beneficiaries named in a will. City of Philadelphia, “Payments, Assistance, and Taxes: Realty Transfer Tax,” accessed May 14, 2021, https://www.phila.gov/services/payments-assistance-taxes/property-taxes/realty-transfer-tax/.

- Orphans’ Court is a division of the Court of Common Pleas that has jurisdiction in matters dealing with the personal and property rights of people who are incapable of dealing with the matter on their own—such as children, incapacitated individuals, and the deceased. Philadelphia Bar Association, “Philadelphia Estate Practioner Handbook: Practice and Procedure Before the Orphans’ Court Division of the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia County (‘the Red Book’)” (2002), 19, https://www.philadelphiabar.org/WebObjects/PBA.woa/Contents/WebServerResources/CMSResources/PEPH_red.pdf.

- D. Patete, clerk of Philadelphia Orphans’ Court, telephone call to The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 6, 2020.

- Pennsylvania 20 Pa. C.S.A. § 3546, https://codes.findlaw.com/pa/title-20-pacsa-decedents-estates-and-fiduciaries/pa-csa-sect-20-3546.html.

- Sharon Wilson, solicitor, Philadelphia Register of Wills, email to The Pew Charitable Trusts, April 8, 2021.

- Philadelphia VIP, “Quiet Title Training Guide,” 16-25.

- Ibid., 36.

- Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, “Medical Assitance Estate Recovery Program: Questions and Answers” (2020), https://www.dhs.pa.gov/Services/Other-Services/Documents/Estate%20Recovery/Estate%20Recovery-Brochure.pdf.

- According to a 2020 survey by insurance holding company Genworth Financial, the median annual cost of a full-time home health aide is $57,200 in Philadelphia, and the median annual cost of nursing home care is $135,415. Genworth Financial, “Cost of Care—Philadelphia Area, PA” (2020), https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html.

- Philadelphia VIP, “Probate Training,” 27-32.

- K. Gastely, managing attorney, Philadelphia VIP, email to The Pew Charitable Trusts, March 2021; Philadelphia VIP, “Tangled Title Fund,” accessed May 14, 2021, https://www.phillyvip.org/tangled-title-fund/.

- Gordon, “Plan. Prepare. Protect.”

- Pennsylvania 20 Pa. C.S.A. § 3132.1, https://codes.findlaw.com/pa/title-20-pacsa-decedents-estates-and-fiduciaries/pa-csasect-20-3132-1.html.

- City of Philadelphia, “City Releases Free Online ‘Fraud Guard’ Tool and Website for Deed Fraud,” news release, Oct. 30, 2019, https://www.phila.gov/2019-10-30-city-releases-free-online-fraud-guard-tool-and-website-for-deed-fraud/.

- Pew calculation; U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Table B25033-Total Population in Occupied Housing Units by Tenure by Units in Structure, 2019 one-year estimates; U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Table B26001-Group Quarters Population, 2019 one-year estimates, http://data.census.gov/.

- Philadelphia VIP, “Tangled Titles.”