The battle for 3000 Funston Street

What does a house interrupted look like?

On a small piece of land in West Austin, you can see the answer: Wooden boards form a rectangle in the center of the lot meant to case a foundation, but it’s a container without anything to contain. The inspector who would have signed off on pouring the concrete was scheduled to come, then told not to show.

On the edge of the lot, metal fencing is in the midst of toppling onto the road. Here the grass hits at the knee and weeds climb. You can’t deliver mail to a plastic sign, but one juts out of the ground in lieu of a mailbox, announcing the place: 3000 Funston St.

The city of Austin more than a year ago started building a single-family home at this address, a plot of land it has owned for five decades. In an attempt to increase access to a wealthy neighborhood, the city planned to sell the home to a low-income family. In a part of town where the typical household earns more than $150,000 a year, the family living here would make half that.

Construction began. But before workers could turn much dirt, neighbors sued.

In their lawsuit filed in January 2020, they argue building on this plot of land is illegal and potentially dangerous. And the neighbors have a case: A judge ordered the city to abandon construction until the claims can be heard at the end of this year. So, for 18 months, 3000 Funston St. has been little more than a plotted foundation.

“The city wanted to do something on it and the people that lived here did not want the city to do something on it,” Nick Comiskey, a neighbor who is not part of the lawsuit, said, summing up the case.

But in a city that has struggled, and largely failed, to build affordable housing in wealthy neighborhoods, this small lot in West Austin is grounds for a bigger story. It’s the site of a battle that has unfolded countless times in this city, raising the question: How do you balance the rights of neighbors to determine what gets built next door with the pressure to build affordable housing where little exists?

‘Nothing To Do With Affordable Housing’

Living near 3000 Funston St. is something few can afford.

The lot is part of Brykerwoods (also written as Bryker Woods), a neighborhood sandwiched between MoPac Expressway and North Lamar Boulevard. Homes here sell for a million dollars or more, and the ZIP code that includes the neighborhood is overwhelmingly white.

“It is no coincidence that many find Bryker Woods a charming neighborhood,” reads the neighborhood association website. “Aspects that can be attributed to this perception are invariably associated with qualities that foster a connection with community,” including modest homes and front porches. In an application for federal recognition of its architectural history, neighbors extolled the district’s large lots, wood-frame homes and near absence of apartments.

Last year, neighbors of 3000 Funston St. formed Friends of Brykerwoods LLC. Under this legal entity, they sued the city and its affordable housing arm in Travis County District Court over the plans for the neighborhood lot.

“This case has nothing to do with affordable housing/low-income families, it’s about following the law,” Trey Jackson, the lawyer representing the group, wrote in an email to KUT.

Jackson won’t say how many neighbors are part of the lawsuit, but in court filings he names three, including his wife. Jackson, it turns out, is also a neighbor.

In court documents, he argues this is a case about flooding and private deed restrictions – particularly, the city’s failure to prevent the former and its refusal to honor the latter.

In an undated video Jackson shared with KUT, a stream of water rushes down the road outside 3000 Funston St. during a heavy rainstorm; the water looks to be at least mid-calf height. In legal filings, he calls the area’s storm sewer system “antiquated and outdated.”

The property in West Austin butts up against the barrier for MoPac. (Photo by Nathan Bernier)

The city confirmed the corner of Funston Street is a “flood problem area,” but said it needs to complete an engineering study before it will start fixing the problem. A representative for Austin’s Watershed Protection Department told KUT it expects to finish this study “sometime next year,” and in court hearings a city staff member said it would likely be five years before any engineering changes could be made to mitigate flooding.

Until that’s done, Jackson argues, neighbors and their homes are in danger.

In legal filings, the city’s attorneys fired back: “Stopping construction based on alleged increased drainage issues would be like using a sledgehammer to do the work of a scalpel.”

Lawyers argue building one home will not significantly worsen the flooding problem. Engineers hired by the city wrote that while a home at 3000 Funston St. would increase how much water drains off the property, it would do so “by a negligible amount.”

The bigger problem, the city contends, is what Austin loses by scrapping one affordable home.

“The city of Austin is in desperate need of affordable housing,” attorneys for the city write in legal filings. “The harm from halting construction outweighs any harm that may accrue to plaintiffs.”

Everything To Do With Affordable Housing

Walter Moreau is so desperate to build affordable housing in West Austin, he’ll proposition anybody.

“If anyone listening out there has a piece of land that’s more than an acre in West Austin, we want to talk to you,” he says, laughing. But he’s very serious.

Moreau is the executive director of Foundation Communities, a nonprofit that builds and maintains affordable housing in Austin. The organization focuses on homes for families to rent, so it needs a good amount of land (preferably not too expensive) on which to build apartment buildings. And that’s hard to find in some Austin neighborhoods.

“We’ve taken the position over 30 years that we want to provide affordable housing in all parts of town,” Moreau said. “But the hardest part of the map to fill in has been Central and West (Austin).”

Put another way: Austin is bad at building affordable housing in wealthy neighborhoods.

The numbers are pretty stark. While Austin has just over 33,000 income-restricted units, more than half of these homes are in the city’s lowest-income districts in East and North Central Austin.

Separately, the area west of MoPac is a veritable affordable-housing desert. There, where families earn some of the highest incomes, you’ll find just 5 percent of the city’s affordable-housing stock.

The city districts where residents earn the least have 10 times the number of income-restricted homes as those districts where residents earn the highest incomes.

Joao Paulo Connolly says the result is that people earning less have fewer choices about where to live, less access to good jobs and few options about where to send their kids to school.

“We know that Austin is a segregated city,” Connolly, who works on housing policy for the Austin Justice Coalition, said. In an oft-cited analysis from 2015, researchers crowned Austin the most economically segregated city among the country’s largest; in other words, it’s a city where you’d struggle to find someone earning minimum wage living down the street from a tech worker.

In 2019, City Council members approved a document they hope will begin to rectify the city’s segregation.

Two years earlier, Austin adopted its first-ever housing plan, including a set of aggressive housing goals: build 135,000 new housing units over the next decade, with about half of these reserved for families earning roughly $60,000 a year.

Not wanting to be outdone by their own ambition, city leaders set another goal: Construct this new low-income housing throughout Austin, but specifically in wealthy neighborhoods that have good schools and great jobs and little affordable housing.

“The idea really is how do we make sure that people have better access to education, health opportunities, work opportunities,” said Awais Azhar, who works for HousingWorks Austin.

Some of Austin’s wealthiest neighborhoods were directed to build, build, build. City leaders assigned District 10, which stretches from MoPac west to Lake Travis, one of the most ambitious affordable housing goals: add nearly 8,500 low-income housing units over the next decade.

It would be an understatement to say the district has, thus far, fallen short.

In three years, builders have erected just 24 affordable homes in this part of town; that’s less than 0.3 percent of the city’s 10-year goal. Meanwhile, some of Austin’s lowest-income districts have outpaced the affordable-housing goals set for them.

“The burden is always left to the districts and neighborhoods that have always carried the city’s affordable-housing stock,” Connolly said. “It’s pretty shocking that we allow this.”

Council Member Alison Alter, who represents District 10, said she was not surprised by these numbers.

“The Council deliberately adopted goals that were inflated and aspirational,” she said. “Many of the staff agreed at the time that the goals were not realistic and the tools that we have in our tool bed are not adequate to meet those goals. This was particularly true in my district.”

Alter said various factors such as high land prices and environmental protections make it difficult to build new housing – particularly affordable housing – in her part of town.

When these affordable-housing goals came up for adoption in 2019, Alter voted in favor. But there was no discussion on the item when it came time to vote.

Put The Housing ‘Wherever Legally Allowed’

For five decades, 3000 Funston St. drew few protests.

The city of Austin bought the lot in 1970 as part of a plan to expand MoPac, the highway that snakes behind the property. There was a house on it back then, but the city had it removed. Save for a plastic playscape erected by neighbors, 3000 Funston has remained vacant ever since.

Austin, on the other hand, has not. In the past 30 years, the city’s population has boomed. Since 1990, Austin’s median household income has nearly tripled to $71,576, but homes now sell for six times what they went for back then. One national nonprofit this year estimated a low-income worker in Austin would need to work nearly nonstop in order to afford a two-bedroom apartment here.

Almost a decade ago, the city estimated it was short 48,000 homes for low-income families, a gap housing experts predict has only grown. The result, some worry, is that people earning less than the median income will continue to leave the city for cheaper rents and easier-to-obtain mortgages.

“In many ways, I worry that the Austin of the future may not have a district like mine, one that’s largely working class and rich in diversity and opportunity,” Council Member Greg Casar, who represents a majority-Latino district in Central North Austin, told Curbed Austin two years ago.

But the Austin electorate has had mixed feelings about paying for affordable housing. A decade ago, voters dismissed almost $80 million in bond money for affordable housing; neighborhoods west of MoPac were the most resounding in their rejection. Since then, though, voters have reversed course, approving more than $300 million in municipal bonds for affordable housing.

When it comes to how to spend this money, affordable-housing advocates get especially excited about building on city-owned land. The reason? Buying land is often the biggest upfront cost; in Austin, an empty single-family lot can easily outrun the price of construction.

Enter: 3000 Funston St.

The city decided three years ago it could use this lot to realize, however incrementally, its affordable-housing plans. Using bond dollars, it would build a three-bedroom, two-story home with a covered front porch. The city planned to sell it as part of a community land trust, where a family owns the house but not the land, thereby keeping down the cost of homeownership.

In a ZIP code where the median sales price of a home hit $1.4 million this year, the city would sell this house for less than $300,000. The city hoped to move in a family before the start of the 2020-2021 school year.

The city planned to build a three-bedroom home at 3000 Funston St. and to sell it to a family making less than the typical West Austin household. (Rendering by Community Powered Workshop)

In an email to KUT, Jackson, the lawyer for the neighbors, suggested that the city instead sell 3000 Funston St. to neighbors, whom he said have offered to buy it. The city could then use that money to build affordable housing, he said, “wherever legally allowed.”

Beyond these comments, Jackson would not answer questions. KUT attempted to talk to neighbors, but almost everyone who answered the door had either not heard of the case or were not willing to talk.

Only one neighbor, who lives next door to Jackson, spoke to KUT.

A pastor who bought a home in the neighborhood several years ago, Nick Comiskey said he did not support the lawsuit.

“It is laughably hypocritical for people that have kind of a progressive political ideology to be simultaneously very restrictive about their neighborhoods and the preciousness of their neighborhoods,” he said.

The city, meanwhile, has acknowledged that going to battle for one affordable home may seem futile when it could be focusing on projects that would house hundreds of families. KUT asked for an estimate of the cost of fighting this lawsuit, but the city said because the attorneys are in-house there is “no existing cost estimate for legal services.”

In the city’s appeal of Jackson’s lawsuit, Mandy De Mayo, community development administrator for Austin’s Housing and Planning Department, said that 3000 Funston St. “may just be a single unit of affordable housing. But every unit counts, particularly given the need. … It makes a difference to the city of Austin, which has declared, through its elected officials, that affordability is a top public policy priority. And it matters to Council District 10 in particular and its goal of increasing affordable housing units in that area of the city – an area which, absent the city’s intervention, will be essentially walled off to affordability.”

Ignoring Deed Restrictions

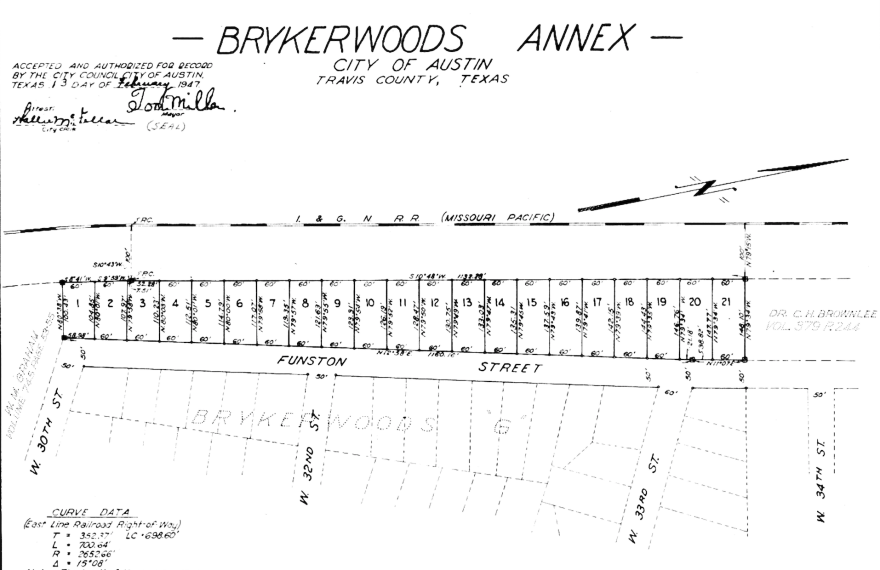

People have been walling off Brykerwoods to affordability since as early as 1947.

That’s when the neighborhood ratified private deed restrictions, also known as restrictive covenants. These documents, many of which originated in the early 20th century, prescribe what homeowners on a certain block can build – or more commonly, what they cannot build.

“Buyers would be willing to accept them because they thought it was going to prevent something hazardous from being near them or give them a desirable neighborhood character, whatever they thought that was,” Elizabeth Mueller, an associate professor at UT Austin’s School of Architecture, said.

Restrictive covenants can be wide-reaching: some limit the minimum sales price of a home, how high a building can go and how much land you need to build a structure. Covenants live with the land, meaning that each owner inherits these rules. Amending them is not easy, often requiring the cooperation of neighbors and the help of a lawyer.

Scan of the neighborhood’s restrictive covenant.

Lawyers for neighbors of 3000 Funston St. argue that when the city bought the lot, it acquired specific rules about what it could build – and in this case, it can’t build anything. According to the restrictive covenant that applies to the block, you need at least 5,750 square feet to build; 3000 Funston stretches to about 4,200 square feet.

The lot used to be bigger. But sometime after the city bought it, the Texas Department of Transportation seized a quarter of the land during the construction of MoPac. (KUT spoke with both the city and TxDOT about this, but neither agency could provide a clear understanding of what happened.)

The city argues it can ignore the restrictive covenant. For starters, lawyers contend the document is void because at least seven other homes on the block are out of compliance; that is, they sit on lots that don’t meet the minimum land size.

“Such widespread violations show that the restriction has been abandoned or waived,” city attorneys wrote in legal filings.

Lawyers also argue that the city’s affordable-housing arm, which owns 3000 Funston St., is a government entity and doesn’t have to adhere to private zoning laws.

Jackson rebuffs both claims.

“It appears Defendant AHFC believes a municipality is ‘above the law’ and it can ignore deed restrictions for a purely political agenda,” he writes in court documents. He says the city was well aware of the neighborhood’s restrictive covenant but went ahead with construction “under the political cover of affordable housing.”

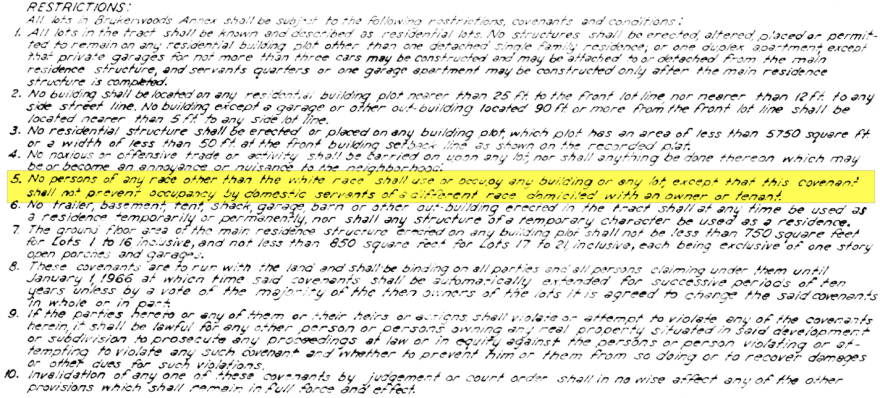

When it was signed more than 70 years ago, the restrictive covenant that covers 3000 Funston St. limited something else: who could live there. “No persons of any race other than the white race shall use or occupy any building or any lot,” the document reads.

Scan of the neighborhood’s restrictive covenant.

While it’s still common to find these racist restrictions in zoning documents, they’ve been legally unenforceable for the better part of a half-century. But housing experts argue they played a key part in modern-day segregation, including in Austin.

“What we see in many, many cities is that these patterns that were set by deed restrictions and restrictive covenants endure,” said LaDale Winling, an associate professor of history at Virginia Tech. “That’s because racial covenants were just the foundation for a wide variety of interventions that reinforced and strengthened racial segregation.”

In the 1930s, the federal government began backing mortgages for many homeowners – but only if they were white and looking to buy in white neighborhoods. This often meant that would-be homebuyers could more easily qualify for mortgages in neighborhoods with racist restrictive covenants.

And thus, white families were granted access to homeownership, while others were excluded.

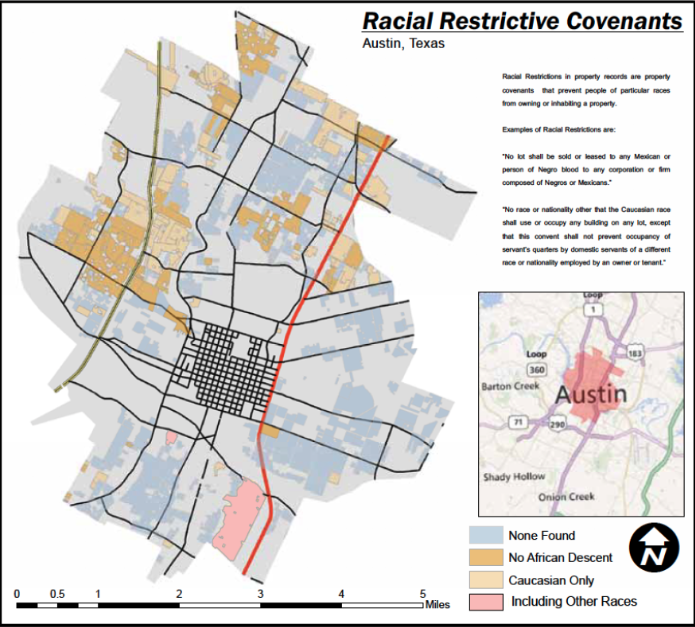

In his paper “Austin Restricted: Progressivism, Zoning, Private Racial Covenants, and the Making of a Segregated City,” Eliot Tretter overlays maps of restrictive covenants in Austin with government maps of neighborhoods “desirable enough” to finance. He found that the federal government refused to issue mortgages to people trying to buy homes in Austin neighborhoods that did not have restrictive covenants, or areas where anyone – regardless of race – could theoretically live.

“What’s obvious is that if you look at the geographies and the segregation patterns, is how much these private forms of restriction played a role in the formation of the city and continue to play a role in the formation of Austin,” Tretter, now a professor at the University of Calgary, told KUT.

Restrictive covenants are still most commonly found in parts of West Austin, which tends to be whiter and wealthier than the rest of the city.

Map by Eliot Tretter

KUT asked Jackson how he felt about going to court over a restrictive covenant that includes racist language. Jackson would not respond to this question or others.

When Travis County District Judge Maya Guerra Gamble directed the city to stop building last year, she ruled that the owner of the house next to 3000 Funston St. would “suffer irreparable harm” if a house were built.

“(The plaintiff) has not adequate remedy at law to prevent Defendant Austin Housing Finance Corporation from its continuous violation of the deed restrictions of the Brykerwoods Annex by erecting a residential structure on a Lot not meeting the minimum lot size,” Gamble wrote. “(The plaintiff) will suffer continuous injury if Defendant continues its construction.”

A Cost To The Community

A Travis County judge will hear the full case against building a home at 3000 Funston St. in December. In the meantime, the cost of building has grown.

This summer, the city asked the construction company it hired to rebid for the project. Citing a monumental increase in lumber prices and the cost of redoing the foundation form installed more than a year ago, Ilcor Custom Builders now says it’ll cost $178,206 more to build the house.

If it gets the go-ahead, the city would likely spend half a million dollars to erect a home it will sell for almost half that. (This cost does not include legal fees.)

“Unfortunately, this delay is going to end up not only costing a family access to affordable housing in a healthy and high-opportunity neighborhood,” said Nicole Joslin, executive director of Community Powered Workshop, the firm the city hired to design the home. “But (it) is also literally costing us as a community more to build that unit.”

The city has been receiving complaints about tall weeds and grass at 3000 Funston. (Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez)

In July, the city’s Code Department received four complaints about tall grass and weeds on the property at 3000 Funston St. As of last week, the problem had not been resolved: dense weeds (or are they bushes?) have pushed their way through the wooden foundation form, obscuring it almost entirely.

The orange fencing between the lot and the street has caved in and the metal bollards that once anchored it to the ground are splayed across the grass. In its demise, the fence took the sign listing the lot’s address with it. Now you can barely decipher the numbers. Is that a 3 or a 5? 3000 or 5000 Funston? Is this the right place?

You’d think no one ever lived here. Or ever would.

This story was produced as part of the Austin Monitor’s reporting partnership with KUT.

The Austin Monitor’s work is made possible by donations from the community. Though our reporting covers donors from time to time, we are careful to keep business and editorial efforts separate while maintaining transparency. A complete list of donors is available here, and our code of ethics is explained here.

‹ Return to Today’s Headlines

Read latest Whispers ›